|

Maserati

|

1914

- present |

Country: |

|

|

The first Maserati took to the track in 1926, taking part in the Targa Florio and in the Italian Grand Prix of that year. The last Grand Prix car to be called simply a Maserati and so entered by the factory competed in 1958. At various times in between, Maserati racing cars were among the fastest and most popular.

These periods of distinction were, however, with the notable exception of the Grand Prix years of the middle 1950s - times when motor racing was in the doldrums. At other times it fell to

Bugatti to provide aesthetic excitement, Alfa Romeo to provide emotional excitement, Fiat and Daimler-Benz and Lotus to provide intellectual stimulus.

Alfieri, Bindo, and Ernesto Maserati

The six Maserati brothers were the sons of a railway a engineer living at Voghera in industrial north Italy. Of those six, Marco became an artist, but the other five all grew up to be engineers, mechanics, drivers, or tuners. Perhaps Carlo and Ettore never became much more, but Alfieri, Bindo, and Ernesto teamed together to develop the business of what in later years might have been called a tuning shop.

The firm was known as the Officina Alfieri Maserati, and was set up in Bologna in 1914 when Alfieri decided to take his independence from Isotta-Fraschini where he was employed as a test driver. The working relationship the firm enjoyed with Isotta no doubt explained why they built racing cars for the older company and, after 1919, when Alfieri and Ettore were joined by young Ernesto, they did the same for the Diatto concern.

Racing Diatto Cars

During World War 1 the brothers had been making spark plugs, but in the early 1920s, the attractions of motor sport seduced them again, and Alfieri gained some useful experience in competition with a car that he built around one bank of a V8 Isotta-Fraschini aero engine. Thereafter, the Maserati brothers began to race Diatto cars extensively, modifying them a lot and demonstrating their competition potential at the same time as the company's own abilities.

This spirit was evident at the second Grand Prix of 1922, at Monza, where the team of new Fiats entered were clearly superior to everything else that most rivals preferred taunts of cowardice to proof of ineptitude, and stayed away. Although firms as distinguished as Ballot, Bianchi, Delage, STD and, it is said, Benz and Mercedes all forfeited their entry fees in the conviction that the Fiats' would enjoy a runaway victory, the Maserati brothers convinced Diatto that valour was more honourable than discretion, and their cars started the race. They retired at quarter distance, while the Fiats won at a canter leaving the sole other entrant (a Bugatti) to trail to the finish a good deal later.

By 1925 Diatto were convinced that the Maserati brothers were capable visionaries, and so they were entrusted with the construction of a new two-liter straight-eight Diatto specifically for Grand Prix racing - however only a year later Diatto took the decision to withdraw from racing, and the brothers took over the cars, reduced their capacity to 1½ liters to comply with the new formula that had to some extent prompted Diatto's decision, and set about making the name of Maserati one to be respected.

The Traditional Symbol of Bologna, Neptune's Trident

The company was properly incorporated, and adopted as its trade-mark the traditional symbol of Bologna, Neptune's trident. With this device blazoned on the front of the car and Alfieri at the wheel, the new Maserati won the 1½-liter class in its first race at the 1926 Targa Florio, and finished 9th overall. This first model of the new make was known as the type 26 and was an interesting amalgam of design features culled from the best of Grand Prix cars (such as the twin overhead camshafts surmounting a supercharged straight-eight engine) and others deriving from sporting road cars in quantity production. With a stroke/bore ratio of 1.13:1 and a capacity of 1491 cc, this engine could produce 125 horsepower at 5300 rpm and this was sufficient to win for Maserati the Championship of Italy in 1927.

The years that followed were a period of motor-racing doldrums during which a succession of utterly futile new (and supposedly internationally agreed) formulae met with nothing but scorn and general disregard on the part of all competitors. What applied in place of the rules was a sort of free formula, an 'anything-goes' arrangement designed to whip up as much support as possible for Grand Prix racing at a time when the famous manufacturers were inclined to concentrate on other problems. Thus; the entry lists were made up of individuals, competing as amateurs for sport.

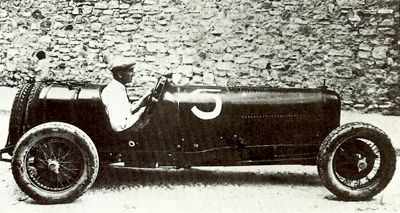

Emilio Maserati in his Type 26.

Emilio Maserati in his Type 26.

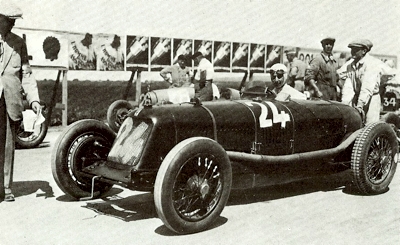

Maserati Type 26B.

Maserati Type 26B.

1936 1500cc Maserati 4CM.

1936 1500cc Maserati 4CM.

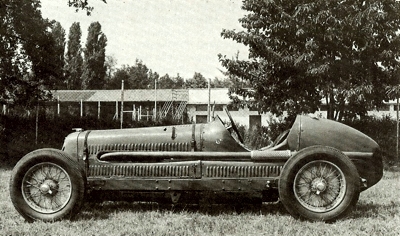

1932 Maserato 16 cylinder V5 competing in the Coppa Acerbo.

1932 Maserato 16 cylinder V5 competing in the Coppa Acerbo.

Dreyfus's Maserati 26M at the 1931 Turin GP.

Dreyfus's Maserati 26M at the 1931 Turin GP.

1933 1100cc Maserati 4CM.

1933 1100cc Maserati 4CM.

1933 Maserati 8CM, which was fitted with a straight-eight 2991cc engine.

1933 Maserati 8CM, which was fitted with a straight-eight 2991cc engine.

Various Maserati 4CM and 6CM racers pictured at a race meeting circa 1937.

Various Maserati 4CM and 6CM racers pictured at a race meeting circa 1937.

Villoressi's Maserati 4CL, with his support race team.

Villoressi's Maserati 4CL, with his support race team.

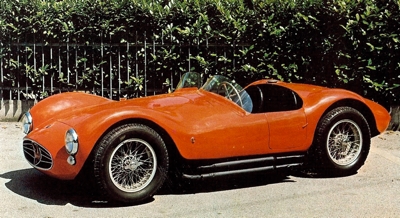

Maserati A6GCS 2 liter six-cylinder racer.

Maserati A6GCS 2 liter six-cylinder racer.

Maserati Type 6` "Birdcage", as prepared for Le Mans by the Camoradi team.

Maserati Type 6` "Birdcage", as prepared for Le Mans by the Camoradi team.

1965 Maserati 200S 4 cylinder.

1965 Maserati 200S 4 cylinder.

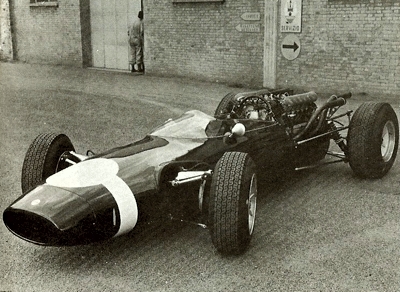

1966 Cooper-Maserati V12 F1 Car.

1966 Cooper-Maserati V12 F1 Car.

1948 Maserati Berlinetta with body by Pininfarina.

1948 Maserati Berlinetta with body by Pininfarina.

Maserati 3500 with body by Touring of Milan.

Maserati 3500 with body by Touring of Milan.

Maserati Merak.

Maserati Merak.

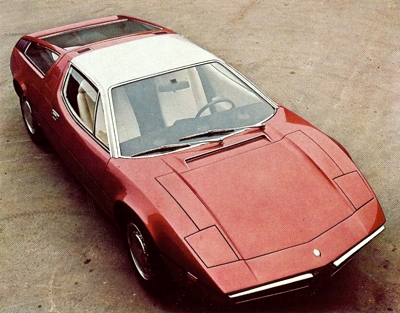

Maserati Bora, which was fitted with a four-cam 4.7 liter V8 producing 310 bhp @ 6000 rpm.

Maserati Bora, which was fitted with a four-cam 4.7 liter V8 producing 310 bhp @ 6000 rpm.

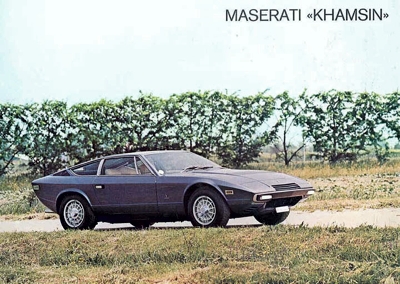

Maserati Khamsin.

Maserati Khamsin.

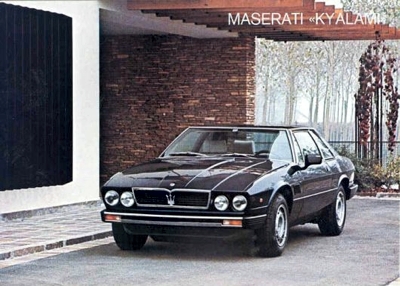

Maserati Kylami.

Maserati Kylami.

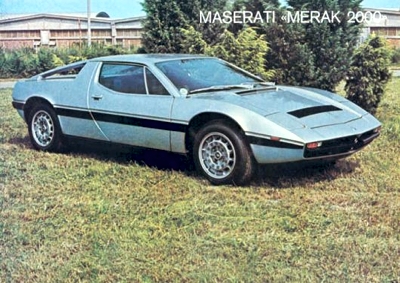

Maserati Merak 2000.

Maserati Merak 2000. |

The Sedici Cilindri

Being anxious to exploit the favourable conditions, the Maserati brothers a car for free-formula events by simply joining two of their straight-eight two-liter engines onto a common crankcase, thus producing a four-liter machine of unrivalled power and publicity value. Officially the car was called the V4, but from what we have researched it seems to have always been called the Sedici Cilindri- - the 16 cylinder - and with 260 bhp at its disposal, it was capable of 155 mph. Its roadholding was not perfected (a common failing of the early Maseratis), but on very fast circuits - it had a natural advantage, and in it Borzacchini won the Tripoli Grand Prix at 91.05 mph in 1930.

Nuvolari Quits Alfa Romeo to join Maserati

By 1930, the 2-Iitre 26B was obsolete and was replaced by a new car, the 8C-2500. It was a car that has been dismissed by some as utterly conventional, but the racing successes it garnered in the ,course of two years should have indicated that there was something special about it. In fact, it was the first Grand Prix car to,' have a separate cylinder head, which was cast in aluminum alloy, while magnesium featured in pre- viously unequalled abundance in castings elsewhere. Encouraged by the successes won by a number of leading drivers, such as Varzi, Fagioli, and Arcangeli, the brothers Maserati embarked on a programme of frenzied work to produce newer, more powerful and even faster cars - to such good purpose that even more notable drivers turned to them, the crowning accolade being when Nuvolari quit Alfa Romeo to join the Maserati works team in 1933, after which he won the Belgian, Nice and Coppa Ciano races.

The 8C-2500 became a 2800 with 198 bhp at its disposal, while the first four-cylinder Maserati, the little 4C-1100, was rapidly replaced by a dual-purpose stripped-out version known as the TR. Amidst all this activity, Maserati somehow managed to contrive a new version of the Sedici Cilindri, this time with 5 liters and well over 300 bhp. It was a time when ultra-fast circuits such as Monza and Avuswere gaining popularity, and the leading contenders all proposed cars in which the provision of ample power took priority over all other considerations.

Bugatti simply made bigger-engined cars, while Alfa Romeo and Maserati coupled two engines together by means more or less untidy - and the Maserati, like the others, was fast and very difficult, not to say dangerous to drive, particularly as the chassis of the day were incapable of dealing with such high speeds and such high power/weight ratios, and compounding the problems was the torque being fed through a live rear axle, and when the full might of such an engine was summoned it made it virtually impossible for the power to be transmitted through the tyres to the road. This was the reason suspension setups became harder and harder, yet in 1932, Fagioli won the Rome and Monza Grand Prix with the car, while Ernesto Maserati finished second in the Italian GP. At the end of the year a record was undertaken with the big 16, but it crashed and the driver Ruggeri was killed.

By 1933, Alfa Romeo were making serious inroads into the supremacy that Maserati had enjoyed in 1931 and, in an effort to restore the status quo, the brothers in Bologna brought out a new three-liter car, essentially similar to the SC-2500 but enjoying 205 bhp and hydraulic brakes. This was the car in which Nuvolari won fresh laurels for Maserati. But times were hard for everyone in motor racing, especially at Grande Epreuve level and, while everybody else was suffering the aftermath of the great depression, the Germans were making a return to the racing with newly designed and very advanced cars - and with blistering performance.

1934 was the first year of the 750 kg formula and, against the technological might of Daimler-Benz and Auto Union, Maserati could do little more than abandon development of the SC-3000 and try a 3.3-liter six-cylinder engine in the old SC chassis. It won Nuvolari a couple of minor events, and achieved little more in 1935 when it was aggrandised to 3.7 liters. More power was clearly needed, and a 4.5-liter V8 known as the RI was used as well in 1935, reaching a speed of 154.9 mph on the Autostrade from Firenze to Mare. However, a year earlier, the two German cars had demonstrated an easy ability to reach 199.

Adolfo and Omer Orsi

This was a poor situation for a firm that depended entirely on being convincing in racing for sales of racing cars (or even super-sports cars) to private customers. The delayed action of the slump was compounded by the death in 1932 of Alfieri Maserati, and the surviving brothers (Bindo, Ernesto, and Ettore) sought some kind of fairy godfather. What they found was a couple of industrialists from Modena, Adolfo Orsi and his son Omer, who bought out the Maserati company but had the sense to keep the three brothers on as privileged employees. The effect of this change in proprietorship was to invigorate the business and stimulate the design of new cars that might hope more effectively to compete with the increasingly doughty opposition they would be facing.

Winning the Indy Memorial Day Sweepstakes in 1938 and 1940

The first priority appeared to be Grand Prix racing, for which the 8C TF was devised, a new car in that it had a new three-liter supercharged engine. Its eight cylinders were, in effect, a duplication of the four-cylinder 1½-liter car's engine, its rear axle was still of the live variety controlled (after a fashion) by half-elliptic leaf springs; yet on sporadic occasions it displayed an altogether unexpected turn of speed, so that in the hands of Villoresi and Count Trossi it sometimes challenged the German cars, albeit briefly and at great cost to its staying power. For some reason, however, it proved able to stand up to the strain of 500 miles around the Indianapolis raceway, and was to prove outstandingly successful there, winning the Memorial Day Sweepstakes in 1938 and 1940.

The Grand Prix supremacy of Mercedes-Benz from 1937 to the war had an unexpected but profound long-term effect. From 1935 onwards, the Italians and indeed all others had fallen back before the regimented onslaught of the newly inspired and materially encouraged German firms, so that the faint echoes of what had once been a great rivalry between nations remained only as an indistinct accompaniment to the rivalry between German teams. Given this dominance, there was a revival of interest in the 1½-liter class which, on a number of occasions, provided a second category of racing. The 1½-liter class cars were relatively simple, and their growing popularity was assured when the Italians conspired to take their own course without reference to the impositions of international regulations.

The first steps towards this were taken in 1938, leading to the announcement by the Italian federation that all races in Italy would be confined to 1½-liter cars in 1939. For their part, Maserati prepared a new 4-cylinder car, using the chassis of the six-cylinder 6CM 1½-liter racer that they introduced in 1936. That car had been numerically popular in Italy, but the introduction in 1938 of the straight-eight Alfa Romeo 158 Alfetta made the 6CM obsolete, and a new four-cylinder engine with four valves per cylinder and a bore-stroke ratio of unity gave the 4CM 220 bhp, a clear 60 more than the 6CM. When the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix was run under the 1½-liter formula (Tripolitania then being under Italian rule), a streamlined version of this car broke the lap record - but it was the quickly built and predictably competent W165 Mercedes Benz that won.

Moving from Bologna to Modena

In 1941 Maserati moved from Bologna to Modena. When the war was over, they made a remarkably impressive comeback, the 4CL being revived to win the first Grand Prix of the new Formula One in April 1946 at Nice. More successes followed, and were reinforced by a new venture, which was the brothers' last for the old firm. This was a sports car, the A6G, with a new six-cylinder single-overhead-camshaft engine in 1½ or 2-liter form. It made its first appearance at the 1947 Geneva Show, but that was the year when the brothers' contract with the Orsi firm expired and they left to return to Bologna, where they set up the Osca company.

The cars from Modena were thereafter Maseratis in name only; but they were apparently none the worse for that, the Orsi family encouraging a rapid and effective development of the 4CL to make it more competitive than ever before. This 1939 car had single-stage supercharging and a simple chassis whose channel-side members were braced by a substantial cast-alloy cross-member which served as oil tank and seat substructure. The independent front suspension by wishbones was sprung by torsion bars, reflecting an increase in the popularity of these media in the late 1930s, while the simple live rear axle was located by radius arms and sprung by quarter-elliptic leaves, emphasising the Maserati tradition of simple construction such as an independent entrant could maintain. Up front was new form of independent front suspension featuring inboard helical springs worked by cantilevered wishbones.

The Maserati 4CL and Juan Manuel Fangio

Its engine was also impressive, with an equal bore and stroke, it boasted a piston area only 6½ percent less than that of the eight-cylinder Alfetta. Better still, it was able to handle the two-stage supercharging that had been introduced by Mercedes-Benz in 1939, making it good for a mammoth 260 bhp at 7500 rpm. In 1949, two of these San Remos were sold to the Automobile Club of Argentina, which entrusted one of them to a driver named Juan Manuel Fangio. He immediately walked off with the Grand Prix of the Mar Del Plata and then came to Europe, where he won the Grands Prix of San Remo and Albi. Other worthwhile victories were scored during the season, but thereafter the cars were outclassed not only by the Alfettas but also by the new Ferraris.

It soon became evident that such failures hardly mattered, as the prevailing Formula One was falling into desuetude and, until the new one scheduled for 1954 came into force, the races of the preceding two years were given over to cars that had hitherto been categorised as Formula Two - that is, cars with un-supercharged engines of two liters displacement. Here was an opportunity for Maserati to compete effectively and economically, and Omer Orsi directed an energetic reorganisation of the firm, which involved the acquisition of the distinguished engineer Colombo. When Fangio drove the Formula Two Maserati to victory in the Italian Grand Prix of 1953, this was the last Grand Prix win ever to be recorded by a car with a live rear axle. It was also the first win of real consequence that Maserati had enjoyed since the British Grand Prix in May 1949, and this may have encouraged the factory to expand the car into a form that was to prove competitive in the new 2½-liter racing formula for more years than any other, a car that was sound enough to win the very first race for which it was entered and to give Fangio the 1957 Championship.

The Maserati 6GA

The Maserati 6GA established itself as the backbone of the 2½-liter formula, even though its roots could ultimately be traced to the 6CM of 1936, but its immediate ancestor was the A6G. It was the first to be developed under Orsi rule after the departure of the brothers Maserati, and this led to a number of important revisions of the design. One was the eradication of the tubular connecting rods that used to fail with dismal frequency, but the bulk of the development work was carried out in the creation of the derivative A6GCM, the additional C and M probably representing Colombo and Massimino (who modified it), which was the Formula Two racer that enjoyed ultimate success at its last available opportunity in Fangio's hands.

The work necessary to bring about this change was largely carried out by Massimino (who was later to be responsible for the V6 Ferrari), and the changes were considerable. The cast-iron crankcase gave way to one of light alloy, carrying a heavily webbed crankshaft in seven plain main bearings. Above this crankcase with its dry cylinder liners was a new head carrying a pair of gear-driven overhead camshafts in place of the original single-camshaft head and chain drive. Increasing the bore and the stroke presented no problems, raising the capacity of the 1½-liter A6G to 2 liters, and the power to 155 bhp and later 177. It was at this stage that Colombo came upon the scene, having already to his credit the Alfetta and the early V12 Ferrari. He took as his immediate brief the extraction of more power from this engine, which he did by concentrating on the shape of the combustion chamber and the effectiveness of the ignition system.

These were important developments, as it was from this engine that the- new 2½-liter Maserati grew in 1954. The new formula then coming into effect permitted the use of any fuel, and if this was to be exploited, it was necessary for the engine to run at an extremely high compression ratio. This was difficult for short-stroke engines, but they were overcome by an extension of Colombo's work on the combustion-chamber design. Taking advantage of this, the Maserati could be run on a complex alcohol-based mixture, providing a power output of 242 bhp. For the promise this offered the engine deserved a chassis less primitive than that of the Formula Two car, and here the most important change was the substitution of de Dion rear suspension for the old grasshopper axle.

The Maserati type 250 F/1

The frame of the chassis was a development of the multi-tubular concept that had begun to enjoy some popularity in the preceding years - not a true space frame but sturdy and effective enough, even if its torsional stiffness was only 300 Ib ft per degree. Add a new transmission to suit the revisions of the rear suspension, and the sum was the Maserati type 250 F /1, a car which was not particularly powerful nor remarkable in any way; yet in 1954, this car, in the hands of a private owner, lapped

Silverstone in 107 seconds, only one second slower than the works Ferraris and two seconds slower than Fangio trying his hardest in the Mercedes-Benz.

In the autumn of that year, the same private owner led both makes in the Italian Grand Prix until a broken oil pipe put the car out of the running with only 12 laps to go and a 20 seconds lead. The story of this car thereafter was one of continued amendment throughout its four years of frontline competition, although the modifications were seldom noticeable and scarcely ever of a major nature. Indeed, prior to the introduction of a new lower chassis at the end of 1956, the only really noteworthy changes to the appearance of the car were the exhaust-pipe layouts and the trial of a steamlined body at Monza in 1955.

The Maserati type 250 F3

The cars that appeared there a year later were new in that they represented a rearrangement of existing components, in order to lower the frontal area. This new chassis was in regular use during 1957, when Fangio returned to the team to win four championship Grands Prix as well as the Constructors' Championship for Maserati and the Drivers' Championship for himself. In that same year, Fangio had the choice, which he never seriously exercised, of another Maserati with a new V12 engine that was frantically powerful, incredibly noisy, and impossibly intractable. Instead, in 1958 a lightweight version of the six-cylinder car was constructed, the type 250 F3, and plans for an even lighter and smaller successor had been prepared.

These had to be shelved however, as the 1957 season had been a hard one for the firm, culminating in a stroke of bad luck in the Venezuela sports Grand Prix. At Caracas, the four cars entered, each a 4½-liter V8 developing about 420 bhp and supplanting six-cylinder cars that had been campaigned in previous years, were reduced to scrap within a few minutes. Masten Gregory's car overturned, Moss rammed an AC, and Harry Shell's car was wrecked by Bonnier's. The cost of this mishap was enormous, aggravated by default on cash payments by Argentina for goods supplied by the Orsi industrial combine, and these losses enforced the withdrawal of Maserati from racing.

Maserati Birdcages

They continued to build sports-racing cars for private owners for some time to come, most of them the types nicknamed 'birdcages' because of the liberal use of small-diameter tubing in their chassis frames. The type 60, a two-liter car, came first in 1959, to be followed by a z.c-liter type 61, and in 1961 this engine was transposed to the rear to create the type 63. They were all very fast, but' often fragile-and they appear to have been con- sidered as something of an unwelcome distraction, for it soon became clear that Orsi wished to concentrate on the production and marketing of touring cars. In fact, this had been an Orsi ambition for a very long time, stimulated by the little six-cylinder cars that had been seen a decade or two earlier, and the first serious demonstration of this intent was presented at the 1957 Geneva Motor Show in the form of the 3500 GT.

The 3500 GT had a twin-overhead-camshaft six-cylinder engine, disc brakes on all four wheels and half-elliptic springs for the rear axle. It was unashamedly a high-performance luxury road car. Later its engine was enlarged, and the power went up from 260 to 270 bhp, in each case with the assistance of Lucas fuel injection. Many of the mechanical components of this car and its successors were made in Britain, including the brakes, the rear axle, and many of the electrics. The programme continued in 1959 with the new 5000 GT, alleged to be capable of 170 mph. The customers, however, were generally more impressed by the Quattroporte four-door car which appeared in 1963, bodied by Frua on an interesting de Dion-axled chassis, carrying a 4.1-liter V8 engine.

Maserati Mistrale Coupe

Even more attractive for those who could content themselves with two seats was the new Mistrale coupe. Other cars of essentially similar character followed and, as the years passed by, their power was increased by augmenting the engine size: by 1967, the six-cylinder

Sebring and Mistrale models had four-liter engines, and in this its final form the simple and elegant Mistrale could justifiably claim to be the last high-class vintage car in production. Things sure changed when Maserati took the covers off the 4.7-liter four-cam V8 Ghibli, a two-door coupe of beautiful proportions. Somehow in the midst of all this, Maserati decided to re-enter motorsport.

Throughout the early 1960s there was always a large, curiously shaped and impressively fast Maserati among the starters in the 24-hour sports-car race at Le Mans, Although they had by this time modernised their sports-racing outlook so far as to produce rear-engined cars for Le Mans, Maserati reverted to a front-mounted engine to make the type 151, with a four-liter V8 engine based on that of the ill-fated type 450. Whether graced or disgraced by a two-seater quasi-streamlined coupe body that looked as though it had been built rather than designed, the 151 was very fast and equally consistently unlucky. All three retired in 1962 and when, for the following year, the engine was enlarged to 4.9 liters it did not last very long, although it led the race during the opening stages, and in 1964 it was timed at a higher speed on the longest straight at Le Mans than any other competitor.

The five-liter type 65, a reversion to the rear-engined Class, did worse. There was however, in that same rear-engined class a clue to the next and last phase of Maserati's long and distinguished racing career. In 1961, the type 63 four-cylinder car had been supplemented by a similar design, with a three-liter V12 engine in its tail. This motor was an enlarged version of that unfortunate 2½-liter V12 that had been seen around the Grand Prix circuits in 1957 and, with its displacement thus augmented, it was just the right size for Grand Prix racing under the new three-liter formula that was to take effect in 1966. Maserati were not going to make a comeback with complete cars, having evidently neither the wish nor the ability to do so, but they could happily supply engines to the new generation of racing-car constructors who built chassis on a shoestring with a welding torch and plugged in engines and gearboxes that might be acquired from other sources.

Maserati found a ready customer in the Cooper Car Company, who had not been doing well in the 1½-liter class for years. The one salient feature of the original V12 engine had been its inlet tracts, which dived down between the opposed banks of valves in each combustion chamber, after the fashion pioneered by Schleicher for BMW, developed by Bristol, and confirmed in racing by Daimler-Benz. In its enlarged 1957 form, the multiplicity of this engine's carburetors had been replaced by fuel injection, the horde of ignition coils had given way to transistorised ignition and, whereas the 1957 methanol-burning engine had yielded high power output at high speeds and very little at lesser rates, the petrol-burning three-liter V12 that appeared for 1966 gave moderately high power at moderately high speeds (about 315 bhp at 950orpm) and had plenty of torque over a fairly wide speed range.

Nevertheless, it was a large engine and a heavy one, giving the Cooper a weight distribution that put no less than 65% of its total mass onto the rear tyres. This is a proportion that would not be thought unusual today, but then Cooper did not have the skills to exploit its potential, and in its early form the car handled indifferently, as well as suffering a large number and variety of minor troubles that caused retirements to come thick and fast among the many private entrants who had seized upon the Cooper-Maserati as an ideal vehicle for getting into top-class motor racing. Not until John Surtees-joined the Cooper works team, after his unhappy departure from Ferrari, were the handling anomalies of the car corrected. But, so successful was the eradication of its difficulties, that a Cooper won the last Championship event of 1966, the balance of probabilities being further upset by another win for the make in the first Grand Prix of 1967.

Joining with Citroen

It was, however, a swan song for the Cooper, which was overweight and under-powered; after abortive experiments with new cylinder heads, the Maserati engine was abandoned, and Coopers played out their last sad days in Formula One racing with BRM engines. In any case, the days of the Maserati concern as it had always been known were numbered. In January 1968, Maserati entered with Citroen into an agreement under which they would co-operate not only in the design of cars but also in their manufacture and marketing. In March of the same year, this agreement was, as initially planned, completed by Citroen's acquisition of a majority interest in the Maserati company.

Thankfully Maserati pursued their own development, and was able to present the new Indy (so named to commemorate the make's victories at Indianapolis) at the Geneva Show. This car was a four-seater closed coupe with bodywork by Vignale, powered by a 260 horsepower 4.1 liter V8 engine which was reputed to make it capable of 155 mph, and was fitted with electronic ignition, an all-synchromesh 5-speed gearbox, and an elaborate disc brake system. Simultaneously, Maserati were developing a new engine, intended for a very advanced car being prepared by Citroen. This was a V6 of unusual 90 degree configuration with the four overhead camshafts being driven by chains that passed between the cylinders so as to keep the engine as short as possible.

The Citroen SM

This dimensional constraint was enforced by the location of the 170 horsepower engine, somewhere in the crowded bonnet of the dramatically styled and technically advanced front-wheel-drive

Citroen SM. The same engine in highly tuned form also powered the surprisingly competitive sports-racers - built by the French rugby international and spare-time racing driver Guy Ligier - who cut his Formula One teeth in a Cooper-Maserati in 1966. Then came the

Bora, an attractive supercar with a 4.7-liter V8 engine, which evolved a lighter and less powerful version known as the Merak, powered by an enlarged and carburetted version of the V6 engine originally designed for the SM, and capable of about 140 mph. Another car to share this power unit was the Quattroporte Il, an SM Citroen-inspired car which, like the SM, was fated to an early grave - in this case, before it even reached its 1975 production date. Like the French car, it seemed the Quattroporte II was just too complicated for general acceptance.

Citroen's marriage with Maserati, however, was not to survive much beyond this point with a confidence crisis separating the two for good, thus leaving Citroen to contend its own problems with Peugeot. The relationship wasn't entirely wasted for Maserati, however, as it led to the manufacture of the four-cam V6 Citroen commissioned for the SM but now used in the Merak and, of course, inherited Citroen's hydraulics technology as used in the

Bora and

Khamsin. Alejandro de Tomaso was Maserati's knight in shining armour, who bought out Maserati and rescued it from possible collapse. During his tenure, development of the de Tomaso Longchamps occured, which would become the

Maserati Kyalami in 1977 and slotted in below the Bora and Khamsin but above the Merak in Maserati's model range. Fiat would go on to take control in 1993, and then Ferrari would acquire 50% of the company in 1997 and, effectively, total management control.

Also see:

Maserati History (AUS Edition) |

Maserati 450S V8 |

Maserati Racing Heritage |

Maserati Car Reviews