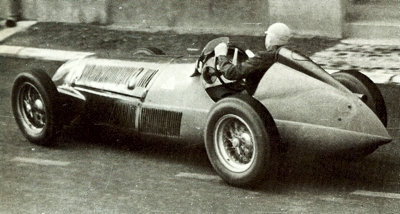

Jean Piere Wmille in action in 1948 during the French GP, at Reims, in his Alfa Romeo 158. If there had been a World Championship that year he was sure to have won it, but he was killed in Argentina the following year before the Championship was instituted.

Jean Piere Wmille in action in 1948 during the French GP, at Reims, in his Alfa Romeo 158. If there had been a World Championship that year he was sure to have won it, but he was killed in Argentina the following year before the Championship was instituted.

Louis Chiron racing in his Maserati in Jersey - that year Maserati were literally the only opposition to Alfa.

Louis Chiron racing in his Maserati in Jersey - that year Maserati were literally the only opposition to Alfa.

Luigi Villoresi in a 4CLT/48 Maserati on his way to victory int he 1948 British GP at Silverstone. He beat Alberto Ascari who was driving a near identical car. The 1948 Silverstone event was a revival of the event last held at Brooklands in 1927.

Raymond Sommer driving through the wet in his Ferrari 125 during the Italian GP at Turin. Villoresi is behind in his Maserati 4CLT, and would eventually overtake Sommer to take second place, with victory going to Wimille and his Alfa.

The 1949 French GP was a sports car event, but Louis Chrion won the country's premier Formula 1 event at Reims in the ageing supercharged 4.5 liter Talbot. |

Naturally, the war put paid to international motor racing, although the Tripoli Grand Prix was held in 1940, and won by Farina's Alfa Romeo at 128.22 mph from the Alfas of Biondetti and the veteran Count Trossi. It was to be some years before racing found its feet again, however. Wars may disrupt and eventually quell motor racing but they have never spelt the end of its continuity. So it was in I914-18 and again in 1939-1945.

World War 2 may have changed the whole way of European life as had the conflict of a quarter of a century earlier and it certainly left Europe in a shattered condition: her motor car manufacturing plants were either destroyed or converted for the production of aircraft and munitions. All through the dark years of this tremendous struggle for power, with bombs raining down on towns and factories, the enthusiasm for motor competitions never wained.

The Bois de Boulogne

Racing was revived by the French in the Bois de Boulogne in September 1945, and international Grand Prix racing was resumed in 1947. The Germans, who had carried all before them before the outbreak of war with their phenomenal Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union racing teams, were not exactly popular at this time. British and American bombers had dealt with their production facilities, and they were in no way able, or allowed, immediately to resume the conflict even with racing cars over the great road circuits.

With Germany understandably in the shadows of morotsport, France were eager to resume motor racing and Italy was well prepared for it. What kind of cars these nations used would depend on the rules and regulations announced in Paris by the governing body of the sport, which was soon revived and operational again.

The new Grand Prix Formula was announced as early as February 1946 and it had been carefully planned to provide for the prevailing post-war situation. Before the war, the Grand Prix racing car had reached a high degree of efficiency, both in the power developed from its small supercharged engines and in its road-holding qualities, which had been enhanced by soft non-leaf-spring suspension systems of an all-independent action, or by the employment of De Dion rear suspension.

Such racing cars were so very fast and accelerative that they called for highly skilled drivers to conduct them and they were a very exciting sort of vehicle to watch when on 'full-song' and engaged in a tense battle with others of the same ilk. However, they had been possible in their final costly pre-war form only because first Mussolini and then Hitler had seen a valuable means of fostering national prestige by racing cars of Italian and German manufacture (but not always driven by nationals) in world-wide international contests.

This had made available to Alfa Romeo and Ferrari and, especially, to Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union, the enormous sums of money needed to research, build, develop and operate such fabulous racing cars. By 1947, the picture was very different. Europe was impoverished and the motor industry, in war-damaged factories big and small, was attempting to salvage something from the aftermath and to get ordinary motor cars back into production.

The FIA

Those who sought to go racing, whether because they thought it good publicity for their customer products, an important laboratory for automotive research, or just because they enjoyed it, had to tread warily. This was if they were to afford the luxury of participation by convincing their mostly impoverished shareholders that it was worthwhile, or even profitable. With these inescapable factors in mind, the new controlling body, known as the FIA, sensibly came up with a Grand Prix Formula which provided for two very different types of racing car to compete together.

It was for cars of not more than 1.5 liters engine capacity supercharged, and of not over 4.5 liters capacity without a compressor or supercharger. This Formula was the one which the former AIACR had been intending to introduce in 1940, had the war not intervened. However, it was a Grand Prix stipulation well suited to post-war conditions. It meant that the expensive, small, high revving superchaged engine (two or multi-stage supercharged) would be pitted against the more easy to render reliable, lazy-revving and big-capacity power unit, providing the latter used normal carburetors.

It was a Formula that was of immediate interest to Great Britain, France and Italy. Britain had been concentrating on voiturette racing from 1934 onwards, with its top capacity figure of 1.5 liters, and Raymond Mays' green supercharged ERAs (English Racing Automobiles) had done very well in this field. France was more inclined, in the terrible plight in which the nation found itself after the end of the war, to hope that big, reliable and enduring sports cars, stripped of their road-going wear, such as windscreens mudguards, hoods, starter motors, lighting equipment, would serve as Grand Prix cars; the non-supercharged 4.5-liter engine-capacity limit looked after them very nicely.

The Italians were in the strongest position in 1947 however, because Alfa Romeo raced the very beautiful and effective little 'blown' 1.5-liter Tipo 158 cars, the Alfettas, before the war and Maserati, a small company devoting themselves to racing-car production, brought out the 6C and then the 4C sixteen-valve, twin-overhead-camshaft, four-cylinder voiturette racing models before hostilities broke out. They were ideally suited to the conditions and rules of the day.

That was the state of technical play as the post-war teams lined up on the grids of circuits that had been abandoned, but certainly not forgotten, during the past eight or nine years, to try their prowess at the resuscitated game of international Grand Prix motor racing. Apart from her economic and productive 'non condition', Germany would not have been allowed by the FIA to return to international motor racing in 1947. Italy was, as has been said, in a fortunate position to resume, but even she had to be content to develop pre-war designs.

Profiting, perhaps, from pre-war German technology, the Alfa Romeo engineers put two-stage super-charging on the Tipo 158 engine, which raised its power output to 265 bhp at 7500 rpm, the blowers being paired in line along one side of the beautifully constructed, straight-eight It-liter engine. This was compared to the 254 bhp at the same crankshaft speed which these engines had been producing back in 1939. Maserati, too, began to experiment with two-stage supercharging and also designed a new chassis, using tubular construction. ERA had brought out the very handsome E-type car of advanced conception; but it was never a success, in spite of having a highly developed version ofthe well known ERA six-cylinder engine that had itself been developed from the hemispherical head, dual-high-set-camshaft Riley Six engine, as raced by Raymond Mays.

The idea of feeding this 63mm x 50mm power unit from a vast Zoller vane-type compressor, and using Porsche trailing-arm front suspension and a De Dion tube at the back, should have paid high dividends but led instead to frustration. France had but her big sports cars to adapt to post-war Grand Prix racing, in the guise of the heavy Talbots and Delahayes, which did not look very promising, but which might not need to pause at the pits quite as frequently as the highly boosted fuel-consuming 1.5-liter racers.

The Centre d'Etudes Technique de l' Automobile et du Cycle

In addition, the French Government, belatedly striving to gain prestige from motor racing, got the Centre d'Etudes Technique de l' Automobile et du Cycle to prepare a world-beating proper It-liter Grand Prix car. This showed enormous promise (on paper) as had its talented designer, M. Lory, who created the great 2-liter V I2 and It-liter straight-eight Delage Grand Prix cars of 1924 - 1927. Called the CTA-Arsenal, as it was to be built at the Government Munitions Factory, the car was a 90 degree V8, 60mm x 65.6mm, with a conventional, two-valves and two-plugs-per-cylinder-head layout, the valves being prodded by two overhead camshafts. However it had all the trimmings including two-stage blowing, of up to jolb per sq in, from twin Roots instruments driven from the front of the engine.

The aim was to achieve 300bhp from this engine which, on the test-bench, did show around 270 at 8000rpm. A chassis with all-round independent suspension was prepared for the CTA-Arsenal but, alas for French hopes, nothing more was heard of it. It was the Tipo 158 Alfa Romeo that was the truly significant Grand Prix car of the period 1947 to 1950. By adopting the sensible attitude of continued advancement of their existing design, instead of messing around with ingenious but untried new cars, Alfa Romeo of Milan managed to outpace (on paper, at least) the impressive Type V 165 Mercedes-Benz V8 of 1939.

Their now very highly supercharged straight-eight engine produced 310 bhp. Its chassis, too, underwent very little modification, although naturally the braking system had to be adapted to the increased performance by fitting stiffer brake drums and getting more heat away from them, thus cutting down the considerable brake fade. .Apart from the big Talbots and Delahayes and the wonderful contribution or Alfa Romeo, there were numerous offshoots of lesser designs during this period of motor-racing revival, such as the Maserati-based OSCA, the Veritas and Meteor, which were really sports cars using pre-war Type 328 BMW six-cylinder engines.

There was also the 2-liter V 12 Ferrari sports car that competed in stripped form as a racing car. The Maserati now appeared under Omar Orsi's direction as the two-stage-blown, tubular-chassis 4CL T model thus reinforcing their chances of success in motor racing. In Britain, Alta were busy with a new Grand Prix car. The pre-war four- cylinder twin-cam engine now had the cylinder dimensions of 78 mm x 78 mm, and was thus of truly 'square' conception, and still with roller-chain-drive to its overhead camshaft. It was used in a brand-new frame with tubular side members and an ingenious method of suspension was by double wishbones. This gave all-independent action when used with rubber blocks as the damping medium, pressed on by bell cranks formed at the lower wishbones.

Unfortunately, for the hopes of Geoffrey Taylor and his little factory at Tolworth, off the Kingston by-pass, near London, this Grand Prix Alta was not a wildly successful racing car. After two years or so of the new regime, Ferrari came up with his Colombo-designed 2-liter racer, which owed much to his satisfactory sports car of that engine capacity. The new GP Ferrari was something of a sensation, because of its very compact size and therefore light weight, into which chassis Ferrari had put a supercharged V12 power pack producing 230bhp. This engine was of 55mm x 52.5mm bore and stroke, so now there was an 'over-square' engine, the first since that of Mercedes-Benz which had trampled on the Italians at Tripoli in 1939.

Like its Alfa Romeo rival, this Ferrari ran at 7500rpm but was content with one Roots supercharger, and a single overhead camshaft operating valves inclined at 60 degrees. It was fitted with a five-speed gearbox, but the handling was not particularly good, the swing-axle rear suspension no doubt responsible for the high degree of oversteer produced on corners. Double wishbones were used at the front, and transverse leaf-springs were employed both front and rear. This, the first of the post-war Ferraris, fell between the winning form of the Tipo 158 Alfa Romeo and the lesser capabilities of the 4CL T/48 Maseratis.

Before World War 2 the predecessors of the FIA, the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus, organised two championships which are the ancestors of today's series. In the mid-1920s a World Championship of Manufacturers was organised, embracing top European Grands Prix. Subsequently Grand Prix racing was in the doldrums owing to, among other things, the economic depression. With the revival of Grand Prix racing in the mid-1930s a European Championship for Drivers was inaugurated.

Racing was somewhat slow to resume after the war had ended, although the delay was not the result of any lack of enthusiasm; all through the dark years of the fighting, bombing, and food and petrol rationing, plenty of enthusiasts made it clear that they wanted to witness racing cars in action just as soon as possible after the foes had been defeated. When hostilities ceased, it was lack of resources which proved the major stumbling block to an immediate resumption of full-scale motor racing.

There was also the inescapable fact that the 1936-1939 era of racing would be a difficult one for the post-war sport to live up to, with fabulous, ear-splitting, very rapid Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union cars still fresh in many memories. Finance to the extent that made such cars, and the costly racing of them, possible, was unlikely to come again, from the exhausted coffers of a war-weary Europe. When racing began again it did so on a modest scale.

The scene was Nice, where they contrived to hold a Grand Prix race in 1946; the race was won by the greying Luigi Villoresi - he has been called the man who was motorracing - at the wheel of a 1

½-liter Maserati. Only three weeks later a similar joyous occasion unfolded at Marseille, with something of the pre-war sounds, sights and scents to thrill the onlookers. It was Raymond Sommer who won this time; also in a 1

½-liter Maserati ; Tazio Nuvolari, by now with failing health, but perhaps still the very greatest of them all, set fastest lap speed and then went on to win at Albi.

The 1946 Grand Prix des Nations

Nuvolari accomplished this with a Maserati, being followed home by Louveau and Raph in the same make of car. In spite of Maserati's early success, the sport had to wait only as long as the return of the Alfa Romeo 'Alfettas' to see a walk-over for the Milanese manufacturer. Ten years after making their racing debut, the splendid Tipo 158s ran away with the 1946 Grand Prix des Nations, which was staged, ambitiously, at Geneva, The winner was Dr Farina, and he was followed home by Count Trossi and Jean-Pierre Wimille, pre-war races again in action; Wimille made fastest lap at 68.76 mph and the race average, set by Farina, was 64.1 mph.

Two more races of this calibre were staged during 1946. There was the Circuit of Turin, longest of the revived races, at 174 miles, which saw Achille Varzi, another pre-war driver, take the honours from Wimille, at 64.62 mph, both in the victorious Alfa Rorneos, with third place filled by Sommer's Maserati, Once again fastest lap went to Wimille, at 73.58 mph - things were warming up. The year 1946 concluded with the shortest of these resuscitated Grands Prix, the Circuit of Milan, over 52 miles ; the race was dominated by the Alfa Romeo team, with Trossi winning, from Varzi and works test driver Sanesi, the winning average being 55.59mph.

The AIEl driven by Varzi, but taken over by Farina, set fastest lap, at 56.7 mph. Motor racing had well and truly started again and all looked forward to. 1947, especially those who had watched Varzi beat Wimille by a mere half- second in that race at Turin. Five races to the prevailing Grand Prix status were organised. There were about twenty lesser events in which the independents, including a number of British drivers, like Reg Parnell and bespectacled Bob Gerard, had a chance of success, but it was the professionals who claimed the limelight. In the Swiss and Belgium Grands Prix the Alfa Romeos continued to make the pace, the order in both races being Wimille, Varzi, Trossi; the average speed of the former race, over 137 miles, was 95.42mph, and at Spa, where the distance was 310 miles, the average was 95.28mph.

In the first of these 1947 contests Maserati had the honour, such as it was, of making fastest lap, when Sommer managed a top speed of 97.03 mph, but at Spa the best time was done by the winning Wimille, at a speed of 101.94 mph. Varzi and Sanesi, in that order, held off the Maserati of Grieco at Bari, the winning Alfa averaging 65.1 mph for the 165.5-mile race, and at the Italian Grand Prix, back to almost former glory, the expected Alfa Romeo grand-slam was seen once again, with Trossi, Varzi and Sanesi in the order of finishing, and the winning speed was 70.29 mph.

The terrors of Milan were absent from the 314 mile French Grand Prix, giving the unsupercharged cars their chance; popular (and pre-war) veteran Louis Chiron pulled off victory in a Talbot, at 78.09 mph, from the Maserati of Louveau. It wasn't GP racing, but in the great

Mille Miglia sports-car contest Nuvolari made a memorable swan-song; although he was by now a very ill person, he defied adversity and heavy rain, to bring a 1100cc Cisitalia home in second place, only a quarter of an hour behind the winning j-liter Alfa-Romeo, driven by Biondetti.

The new Formula began to take hold for the 1948 racing season. In the European GP, held at Berne, Switzerland, it was the compact, highly- supercharged, Alfa Romeos that dominated, driven into first and second places by the experienced, pipe-smoking Trossi, and Wimille, the former averaging 90.81 mph from start to finishing-flag, and the latter setting up the fastest lap of the Swiss circuit, at 95.05 mph. Third place was secured by Villoresi in a Maserati. These Alfa Romeos continued to be the racing sensation of the age, and in training for the French Grand Prix of 1948 at Reims, Wimille lapped at 112.2mph and although in the event he was not able to do better than 168.14.mph, this gave him victory, at 102.1 mph; Wimille's team-mate Sanesi was second and the rising star, Alberto Ascari (son of the Antonio Ascari who had been killed at Lyon in this very race, before the warjthird, also in an Alfa Romeo.

In the Italian GP Wimille won again, after the other Alfas had met with trouble, from Villoresi's 4CLT Maserati and Sommer's Ferrari, at 70.38 mph. The marque from Milan had been placed 1-2-3 in the Monza GP, in the sequence Wimille, Trossi, Sanesi. The race-average was a remarkable 109.98 mph and Sanesi lapped at 116.95 mph, with one of these 1500cc cars. Achille Varzi had been killed while practising at Berne, when his Alfa Romeo overturned, Wimille was the victim of a fatal accident in South America, at the wheel of a Simca voiturette, and during 1948 Trossi died from cancer.

At the difficult round-the-houses Monaco Grand Prix Maserati returned to the forefront, when Farina won at 59.61 mph from Chiron's Talbot, with de Graffenreid, the keen Swiss driver, third in another Maserati. The winner lapped the Monaco course at 62.32I1lph. The British Grand Prix was run over the new aerodrome circuit at Silverstone and was a victory for Villoresi, who averaged 72.28 mph and also set fastest lap, at 76.82 mph. His new Maserati team mate, Ascari, backed him up with second place, and third place went to Bob Gerard's ERA.

Hermann Lang

Perhaps it was the loss of some of their best drivers that persuaded Alfa Romeo to drop out of racing in 1949. The Tipo 159 racers, which were then scattered unceremoniously about the factory, or tucked into odd corners gathering dust, had started in 19 races since 1938, of which they had won 16, finishing I, 2, 3 on no fewer than ten occasions. They suffered defeat only at the hands of Maserati (twice) and the W165 Mercedes-Benz of Hermann Lang. It was an impressive record. With Alfa Romeo out of contention, and the strong, level-headed, enormously talented Juan Manuel Fangio now occupying the driving seat of a Maserati, the Italian make dominated the 1949 races: Fangio won at San Remo (62.78 mph for 178 miles) and at Pau (52.7 mph for 87 miles), being followed in by the Maseratis of B. Bira and Baron de Graffenreid in the former race, and by Gerard's ERA and Rosier's big Talbot in the latter.

Bira, the diminutive Siamese Royal driver who had been sponsored and managed by his cousin Prince Chula before the war, was still on form, and he made fastest lap at San Remo, at 64.66 mph, and repeated his show of speed at Silverstone in the British Grand Prix. This race was a victory for E. de Graffenreid in a Maserati, with the irrepressible ERA second, and Louis Rosier's Talbot placed third, an interesting mixed outcome, the winner averaging 77.31 mph. In the Belgian Grand Prix Rosier came into his own, winning with a Talbot at 96.95 mph, outclassing both Villoresi and Ascari in their Maseratis.

Dr Farina also in a Maserati, since Alfa Romeo's withdrawal from racing, made fastest lap at over 101 mph. The scene then shifted to the Swiss GP and here Alberto Ascari was in the ascendant, coming first past the finish; Farina's Maserati averaged a fraction more than 95 mph to establish the fastest lap speed, and the winner himself averaged 90.76 mph for this r Sr-mile contest. This year the Italian GP at Monza took on the mantle of the European GP and it was another victory for the chubby, Roman-nosed Ascari. He was now in a Ferrari, and averaged over 105 mph, though in practice he had lapped even faster, at 112.72 mph. Phi-Phi Etancelin was second in a Talbot and Prince Bira third in his Maserati.

The GP de France had previously been won by Chiron's Talbot from Bira's Maserati, and Britain's Peter Whitehead had taken third place in a Ferrari. Whitehead was later to go on to victor.y in that years Czechoslovak Grand Prix at Brno. At the converted Silverstone airfield circuit, the newly formed British Automobile Racing Club had revived, under its new colours, the pre-war Junior Car Club's International Trophy Race, this being won- in 1949 by Ascari, at 89.58 mph, after he had lapped triumphantly at 93.35 mph- Silverstone was already a fast course. Ascari was followed home by his teammate, Villoresi, but only in third place, for Farina had forced his Maserati between the two Ferraris.

So it was that motor racing started up again in the post-war years. It was well established by the time the 1950 season opened. A World Championship for Drivers proposal was considered by the CSI in 1949. At first it was agreed that in the following year a series of national Grands Prix would qualify towards the championship plus the Indianapolis 500 Miles in the US, this country's nearest equivalent to a European Grand Prix. The European races were to be to the current Grand Prix formula - at that time 1

½ liters supercharged or 4

½ liters un-supercharged - but Indianapolis ran to the AAA's 3 liters supercharged / 4

½ liters unsupercharged formula.