A Liscence to Kill

MORS is the Latin word for death, a coincidence which did not escape the notice of a motorphobe Member of Parliament at the turn of last century, who claimed that the name implied that Mors drivers had the licence to kill anyone who crossed the path of their cars.

Nor was the situation alleviated by the fact that the company was apt to use the Latin tag Mars ianua vitae in their advertising. It is, however, difficult to see a deaths-head in the hirsute and rubicund features of Emile Mors, the marque's progenitor, who in Victorian days had risen to become one of France's leading electrical engineers, heading one of the country's biggest telegraph, telephone and electrical-equipment factories.

In the late 1880s, Mors became aware of Leon Serpollet's experiments with steam vehicles, and built a light three-wheeled steam carriage which was the first of its kind to have an oil-fired boiler (Serpollet was still using coke as a fuel); eighteen vertical fire-tubes were arranged over a similar number of wicks which could be raised or lowered to regulate the generation of steam.

The steam was superheated in a copper coil before being passed to the vertical rear-mounted engine, which drove directly from crankshaft to rear wheels. The car, which had rack-and-pinion tiller steering, was shown at the 1889 Paris Exposition and again at the 1900 retrospective exhibition.

Seven or eight of these vehicles were built, and in 1904 one was still in regular use by an enthusiast in Vendome for travelling between his house and the local railway station - a good achievement for that time. However, Mors realised the limitations of this design and, for the time being, devoted himself to the development of petrol motor trucks for portable railways, several of which were built in 1892-3 to a patent taken out in England.

In 1895 Emile Mors built his first petrol car, with a rear-mounted V4 air-cooled engine (which had, however, water-cooled cylinder heads) designed to minimise vibration. In the interests of simplicity and reliability, belt drive was adopted; ignition - of course - was electric, by coil and dynamo, with a battery used to boost the dynamo for starting. Once the car was running, the dynamo supplied all the ignition current, the surplus being used to recharge the battery.

The 1897 Paris-Dieppe Race

Two years later, the marque made its first appearance in competition, when Emile Mors himself drove a two-seater 5 hp Mors to seventh place in the 106.2-mile Paris-Dieppe Race on 24 July 1897, averaging 19.6mph; two four-seater Mors driven by Mouter and Viard were sixth and seventh in. their class, although their average speeds of I2.2 and 11.9 mph were hardly spectacular.

The following season saw the end of Emile Mors's brief career as a racing driver: he was lying third in the Paris-Bordeaux race when he collided with a cart near Angouleme, Mors and his co-driver, Toussaint, were thrown from the wreck, and their team-mate, Levegh (the nom de course used bythe rich and consumptive Alfred Velghe), gave up his chances of winning by stopping to give first aid to Mors, who had broken his collarbone.

That year's racing Mors cars were belt-driven, with the V4 engine at the rear.

The next year saw the company's first true racing cars, designed by Mors' new chief engineer Henri Brasier. These followed the contemporary Panhard layout, with front-mounted vertical in-line four-cylinder engines of 4.2 liters. Then, commented the Parisian Motor Review, there began a struggle for supremacy that forms the most brilliant page in automobile history, the new Mors, built purely for speed, eclipsed everything in that year by winning the events in which it took part, and raised the record in long distance races to 37 miles an hour'.

That record was made in the last race of the 19th century, the 163-mile Bordeaux-Biarritz, won by Levegh; his car attracted attention by its distinctive appearance, with its wedge-shaped bonnet, unlike any other racing car.

'Panhard and Mors,' continued the Motor Review, 'now fought a valiant battle for supremacy, M Mors coming out in 1900 with 20 hp cars piloted by men like Levegh and Fournier.

The public interest in the rivalry between the two firms was so intense that the popularity thus given to racing did a vast amount of good to automobilism, and the struggle itself had the still more important result in compelling the makers to surpass each other in the building of speedy vehicles'.

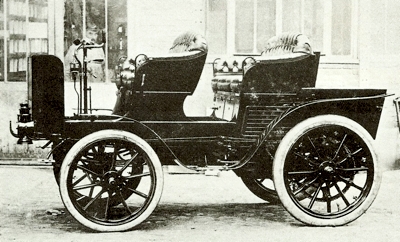

1899 6 hp four-cylinder Mors.

1899 6 hp four-cylinder Mors.

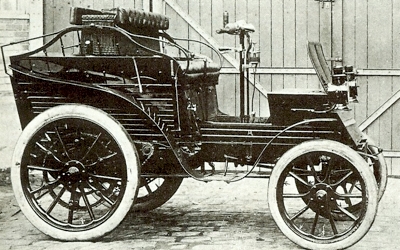

1897 6hp Two-Seater Mors.

1897 6hp Two-Seater Mors.

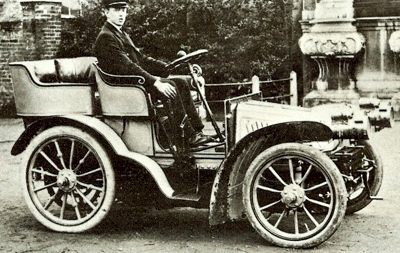

By 1901 the Mors were starting to look more like cars, and less like carriages.

By 1901 the Mors were starting to look more like cars, and less like carriages.

1902 Mors Paris-Vienna Racer. It used a 9.2 liter engine with chain drive.

1902 Mors Paris-Vienna Racer. It used a 9.2 liter engine with chain drive.

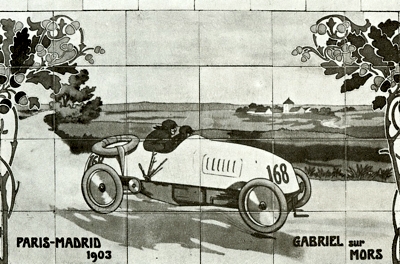

Tile drawing of 1903 Mors competing in the Paris-Madrid race.

Tile drawing of 1903 Mors competing in the Paris-Madrid race.

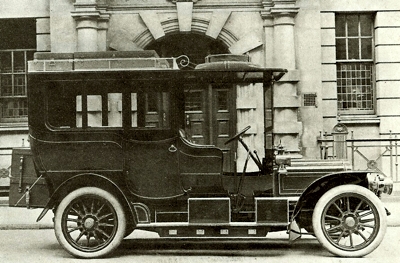

1906 Mors with coachwork by Barker.

1906 Mors with coachwork by Barker.

A 1908 Mors Tourer - although the company was in decline, they still produced wonderful cars.

A 1908 Mors Tourer - although the company was in decline, they still produced wonderful cars. |

The Mors Petrol-Electric

Just to show that the company had not entirely forgotten its origins, however, Emile Mors built an experimental petrol-electric car, one of the very first of its type, around this time; he also experimented with a magnetic clutch a year or so later. On the touring front, a new flat-twin light-car was available from 1899, although it had low-tension magneto ignition in place of the ingenious dynamo.

The marque's racing successes obviously sold cars: when the firm began production on a serious scale, in 1898, the works employed 200 workmen. Six years later, the total had risen to 1200, and two cars per day were being turned out in the immense factory in the Rue de Theatre.

By 1901, the touring Mors had in-line power units like the racers (although they retained the old air-cooled cylinder layout until 1902), chain drive and a primitive form of multi-choke carburetor also forming part of the specification.

The company's racing prestige had suffered a wounding blow when, despite convincing performances, Mors had failed to be selected for the French team for the 1900 Gordon Bennett. So, Levegh, in one of the new 7.3-liter Mors racers, followed the contestants in a 'freelance' capacity, and would have come second had he been officially taking part.

The Paris-Toulouse-Paris Race

ust to show it had not been a fluke, Levegh won the 837-mile Paris-Toulouse-Paris race against tough opposition, finishing well on elapsed time ahead of his nearest rival, Pinson, in a Panhard, although the Panhards of Pinson and V oight arrived at the finish actually in front of the Mors.

Officially, the racing Mors for the 1901 season were rated at 28 hp, although their drivers reckoned that 60 hp would have been nearer the mark. Proof positive that Emile Mors' policy of 'build bigger ... build faster' was the right one for that stage of automotive technology came with Fournier's victories in the Paris-Bordeaux and Paris-Berlin races that year.

Mark you, a cyclist nearly changed the course of motoring history when he dropped his paraffin lamp into a pool of petrol lying under the Mors just before the start of Paris-Bordeaux, but the flames were extinguished before more than superficial damage occurred.

Had Mors bothered to enter Fournier rather than Levegh for the Gordon Bennett, organised concurrently with Paris-Bordeaux, they would have won it, as the highest-placed British contestant, Girardot (Panhard), was only ninth in the main event.

Unfortunately, Levegh was eliminated by gear troubles near Tours. Fournier won Paris-Berlin in convincing style, arriving half-an-hour ahead of Leonce Girardot, 'the eternal second', who was driving a Panhard. De Knyff (Panhard) was third, while Mr Designer Brasier was fourth, at the wheel of one of his own creations.

Just how big a part luck played in motor racing was amply proved when Fournier started up his car for a triumphal drive through Berlin after the race and the driving chain broke! Despite the introduction of the 1000 kg weight limitation for 1902, Mors once again increased the engine capacity of their racers.

The Four-Speed Transmission

These also featured a new design of four-speed transmission, which gave direct drive on top gear, plus a pioneering use of dampers, the first real attempt to deal scientifically with the bounding and leaping of the racing-car when at high speeds, a fruitful source of power loss. Two hydraulic dampers were fitted to the front axle, four to the back, and the Mors cars did indeed prove very fast; but trouble with the new gearbox eliminated Fournier from Paris-Vienna after he had averaged 71 mph from Paris to Provins, and then passed an express train as if it was standing still. Indeed, the Mors mortality rate in this race was alarmingly high, though it was said that 'the Mors prestige was not in the least decreased by their failure in Paris-Vienna'.

1902 wasn't really a Mors year, as Brasier left to join Georges Richard. Then their leading driver, Henri Fourfiier, transferred his allegiance to the new Hotchkiss company, which then added insult to injury by enticing Brasier's colleague, Terrasse, to join them as designer; he then created a racing Hotchkiss that was more Mors than the genuine article. A third member of their drawing office was to resign a year or so later; he was Charles Schmidt, who emigrated to America to design Continental-style cars for Packard.

Meanwhile the Mors company's racing career had reached a glorious peak with Gabriel's victory in the notorious Paris-Madrid; the car with which he averaged 65.3 mph from Paris to the race's abandonment in Bordeaux was one of the new Mors Dauphins. The company built 13 Dauphins in all, and their design represented a considerable technical advance over anything Mors had done before. They had pressed-steel chassis and an inlet-over-exhaust engine with all valves mechanically operated from a single camshaft, and, most strikingly, bodywork 'of the best racing design, quite smooth from radiator to back axle, in shape not unlike an upturned boat'.

But this wind-cheating shape was abandoned in 1904, when the company's racing cars acquired the new 'shouldered' pattern of honeycomb radiator that had just been introduced on the touring Mors models (and which, almost certainly, was the inspiration for the classic Packard radiator shape, which appeared after Schmidt had joined the American company). These 110 hp, 13.6-liter cars were fast-one of them recorded a speed of 108.5 mph during 1904 - but Emile Mors anticipated even larger, faster racing cars.

Mors and Panhard Supremacy Declines

However, the days of brute force were passing, and so were the days of Mors and Panhard supremacy. Mors did not even bother with the 1905 Gordon Bennett, raced not at all in 1906 and made only token appearances in 1907 and 1908, culminating in a failure-strewn attempt on the 1908 Grand Prix which even the presence of Camille Jenatzy in the team failed to enliven.

The company's touring cars followed the fortunes of the racers: when Levegh and Fournier were dominating the lists, Mors private cars were in wide demand, rivalling Mercedes as the dernier cri in motoring fashion. But when the company gave up competition, the touring cars went into a gentle decline. Not that there was anything cheap or shoddy about the latter-day Mors; on the contrary, they tended to bristle with technical ingenuities like M Mors' compressed-air starter, which appeared around 1906, the same time that the company offered that ingenious form of windscreen known as the Pare-Brise Huiller after its inventor, a Mors director who was perhaps more famous under his nom de course of Gilles Hourgieres.

There was also the Mors clutch: 'By the action of the clutch spring a cone is pressed forward between two levers, which tightens two bands lined with cast-iron segments round a steel band fitted to the flywheel. A very gradual engagement is obtained by this device, which has the merit of imposing no end thrust on the crank shaft'. And 'this device' was to remain a feature of all Mors cars over the next 20 years.

Andre Citroen becomes Managing Director

Another technical innovation of pre-World War 1 was the herringbone-pattern final-drive gearing that was the obsession of the company's new manager, Andre Citroen, and which he would adopt, in stylised form, as the symbol of his own company in later years. Citroen took over the running of Mors after the company had all but collapsed in the 1908 depression, and under his influence sales began to pick up, aided, no doubt, by the decision of the British agents (Jarrott & Letts, of Great MarIborough Street) to take the entire output of the 10/15 light car introduced at the end of 1909.

But even the activities of le Petit Juif couldn't reverse the process of decay. The first signs that the recovery had only been temporary came in 1912, when the company began to supplement its own power units with Silver Knight sleeve-valve engines supplied by Minerva of Antwerp (whose London agent, Danny Citroen, was related to Andre of that ilk); two years later Mors was totally beknighted save for the smallest model and a new side-valve 17/20 hp sporting car of handsome appearance.

After the war, it was nothing but decay and sleeve-valves: Citroen took over the Mors factory to produce his Type A, though the older marque continued a sort of existence for a few more years. Indeed, the Mors SSS (Sans Soupapes Silencieuse) was a rather fine car, with a radiator similar to the contemporary Bentley and four-wheel-braking from 1921. Minerva engines of 3.6 liters (plus, from 1922, a 2-liter unit) were used, but by 1926 production of Mors cars had just petered out.

Mors Electric Cars of World War 2

The name was revived briefly during the war for a range of electric cars, though these were about as relevant to the company's history as the modern electric golf carts built in America under the Chad wick name are to that marque's supercharged Great Chadwick Six of 1908. Perhaps the same veil that should be drawn over the wartime electric Mors should also cover the last vehicles to bear the name, as these were depressing motor scooters called, optimistically, Speed, built in the early 1950s before the marque finally succumbed to the rigor mortis that had been threatening for almost half a century.