|

Mille Miglia 1000

|

1927

- 1957 |

Country: |

|

|

OVER THE YEARS the Mille Miglia has deyeloped a reputation as one of the most difficult, tortuous, yet romantic races ever devised. It spanned a period of only 31 years, from 1927 to 1957, yet each race often packed in more drama and courage than a whole season of Grand Prix races. Automotive history books are filled with interviews taken of those who were fortunate enough to participate or merely watch from the sidelines.

Possibly only in Italy could such a long road race have persisted into the late 1950s, as most other countries had long before abandoned road racing and even placed severe restrictions on rallying. It was only an accident in the 1957 race, costing the lives of nine spectators, that forced the Italian Government to stop the event.

Giovanni Canestrini, Count Aymo Maggi, Franco Mazzotti and Renzo Castagneto

The idea for the Mille Miglia (1000 miles) came from four Italian enthusiasts who desperately wanted to emulate the Le Mans 24-hour race which had started in 1923. The four men, famous journalist Giovanni Canestrini, Count Aymo Maggi, Franco Mazzotti and Renzo Castagneto decided that Italy's answer to Le Mans must be a road race.

Since Castagneto was the secretary of the Brescia Automobile Club, the town of Brescia naturally had to be the starting point. The route mapped out was a figure-of- eight course round Italy, with the crossing point of the eight at Bologna, the start and finish being in Brescia. A great number of difficulties had to be overcome. The Government had to approve the scheme, various automobile clubs had to arrange checkpoints and organise refuelling depots and the police had to block off all access points and keep spectators off the road-a difficult job to organise over a few miles, but for 1000 miles of ordinary main road it was a Herculean task.

The first race, in 1927, was run in an anti-clockwise direction round Italy, the route running from Brescia down to Piacenza, then inland to Parma, Modena and Bologna. The really hard work started after Bologna for the drivers had to cross the Appenine mountains to Florence before tackling the hills of Umbria down to Rome. From Rome the course turned east across the Abruzzi mountains to Ancona on the Adriatic coast, where the route turned northwards up the flat coastal strip, via Pesaro and Rimini, before turning inland once more back to Bologna then circling north via Padua, Vicenza and Verona and returning to Brescia. The actual distance was 1004 miles.

It was obviously inadvisable to have a massed start at Brescia so the cars were set off at intervals, with the smallest and slowest cars starting first. This gave faster drivers a great number of problems since they had to pass many slower cars on the poorly surfaced and narrow roads in the mountains, but the race was an immediate hit with both drivers and spectators alike even though the roads were theoretically still open to normal traffic.

Minoia and Morandi's OM Take The Honours

Winner of the first race was the OM of Minoia and Morandi, at an average speed of 47.99 mph, ahead of two other OMs. The relatively low speed illustrates the difficulties of the course; it. took the winners nearly 21 hours of virtually non-stop driving to finish the race. Although the era of the riding mechanics in Grand Prix races had come to an end they were still used in sports-car races, and in the Mille Miglia many cars had two drivers, for most men found they were unable to race for virtually a whole day without respite. Some drivers took a mechanic who could also give route instructions and take a spell at driving on the straight coast roads of the Adriatic, leaving the difficult mountain sections to the number one driver.

Giuseppe Campari and Giulio Ramponi

The Italian manufacturers quickly realised the publicity value of the Mille Miglia and a number of works entries were made in 1928. The race attracted many millions of spectators who turned the day into a great festive occasion, so manufacturers had a large captive audience of potential buyers. Alfa Rorneo entered the 1928 event in some force, victory going to the car of Giuseppe Campari and Giulio Ramponi at an average speed of 52.27 mph, followed home by an OM and a Lancia.

The Campari won the 1929 race, once again accompanied by Ramponi, their average speed rising to 55.69 mph. An OM was second and another Alfa Romeo third. Minor changes in the route were made each year, to cope with road works and deviations asked for by local authorities, but the distance rarely changed by many miles, although it gradually increased.

In 1930 the distance had crept up to 1018 miles and the event provided Tazio Nuvolari with one of his first great successes. He had been invited to join the Alfa Romeo team for the 1930 season and one of his first events for them was the Mille Miglia, which was traditionally held in early April. Accompanied by Guidotti, who later became team manager for Alfa Romeo, Nuvolari intended to drive his 1750 cc 6C Alfa Romeo single handed, relying on Guidotti only for signals to show dangerous parts of the route and for passing his food and drink.

Nuvolari was up against some formidable opposition, notably his team mates Campari and Varzi, but there was also Caracciola in a Mercedes-Benz and Arcangeli in a 2-liter Maserati. The Alfa drivers practised the route over-and-over, none more so than Nuvolari who was unfamiliar with the car. On the fast stretch down to Bologna Arcangelli led, but in the misty mountains of the Appennines Nuvolari showed a sixth sense for the road direction as he flung the car over gravel strewn roads.

Alfa Prove Handling Beats Out-And-Out Power

Guidotti confessed afterwards that Nuvolari's speed in virtually zero visability terrified him. Although the little Alfa sports car could barely exceed 100 mph, it cornered like a dream and Nuvolari took the lead through the mountains. His only refreshment came from a flask of sweet tea, which had been fitted up with rubber drinking tubes, and the occasional piece of orange or barley sugar that Guidotti passed him. On the stretch to Rome Varzi regained the lead, a position he held until the Adriatic coast was reached.

With the relatively straight and well surfaced coast road to come Varzi felt confident of holding his two-minute lead, but Nuvolari began driving like a madman, taking every bend as fast as was humanly possible, using his famous over-steering, tail-sliding technique to the full. The two minutes were gradually eaten away and, as Varzi had started a minute before Nuvolari, the 'Flying Mantuan' had only to hold station to win; but he ignored Guidotti's pleas to ease off and as darkness fell he pushed even harder.

At the town of Peschiera Nuvolari caught Varzi'scar, but Varzi was unaware of Nuvolari's presence as they rushed through the lighted streets of Peschiera on the shores of Lake Garda. To Guidotti's horror, Nuvolari switched off his headlights when they emerged into the darkness outside the town and he followed Varzi by means of his tiny red rear lamps. Still blissfully unaware of how close his rival was Varzi ate up the last few miles to Brescia, but with only three kilo- metres left, Nuvolari switched on his headlights and streaked past Varzi to reach the finish first. It was one of the first signs of the bravura which became a Nuvolari trademark in years to come. Nuvolari had averaged 62.51 mph and had sat at the wheel for over 16 hours without relief.

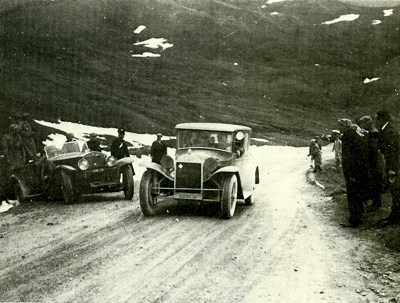

The start of the first Mille Miglia, on the 26th March 1927 at Brescia. The winning car was the OM of Minoia Morandi, at an average speed of 47.99 mph.

Minoia Morandi's OM, winner of the 1927 Mille Miglia. This photo we believe was taken at the Raticosa Pass.

This is a Lancia, photographed during the 1929 Mille Miglia, and with one of the few women drivers at the wheel, Mimy Ayhner.

A photo recorded as taken during the 1931 Mille Miglia, transversing the bridge spanning the river Panaro at Modena.

The victorious Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 of Borzacchini and Bignami in 1932.

Even though there was a war on, the event was still run in 1940. The only foreigh competition was, naturally enough, NAZI Germany, who took out the event with the BMW 328, driven by Baron von Hanstein and Baumer. This was the sister car of Cortese and Lurani.

Piero Taruffi's Ferrari overtaking a Delahaye in pouring rain in front of the crowd at Vicenza.

|

The Mille Miglia Legend Grows

A legend had quickly grown up around the Mille Miglia that no foreign driver or car would ever win the race because of the high degree of local knowledge required, but the myth was shattered in 1931 when Rudolf Caracciola brought his SSK Mercedes-Benz to the race and won as he liked, while the new 2.3-liter eight-cylinder Alfa Romeos suffered continual tire trouble. Nuvolari, exhausted from changing eighteen wheels, finished ninth. After 1931 Alfa Rorneo and Italian drivers re-established their supremacy, winning every event until 1938 - not only winning them, but taking first three places except in 1937 when a Delahaye finished third.

The 1932 race gave victory to Borzacchini and Bignami in a 2.3-liter Alfa, after some of the leading names had dropped out. Nuvolari was fighting for the lead with Caracciola and Varzi, but as he went through Florence, Nuvolari saw a wrecked car on a bend; he quickly snatched a glance at it to see if it was a team mate's car and in that split second he lost control and crashed his own car, only a few yards past the other wreck! In this race young Taruffi snatched the lead briefly in his Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeo, but his car lost its oil pressure and he retired.

For 1933 Nuvolari was accompanied in the Mille Miglia by his friend and mechanic Decimo Compagnoni. They drove a Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeo, now that the factory had withdrawn from racing, and their 2.6-liter Monza Alfa Romeo proved good enough to win. Despite losing the complete silencer system, Nuvolari kept the car in the lead for the whole race, winning by no less than 27 minutes at an average speed of 67.46 mph, despite a good deal of rain in the mountains. Second was the Alfa of Castelbarco/Cortese with Taruffi/Pellegrini third in another Alfa.

MG's Enter The 1933 Mille Miglia

A team of MG's was entered for the 1933 race, a class victory being gained by Captain George Eyston and Count 'Johnny' Lurani. The weather in Italy in April tends to be capricious. Sometimes warm sunshine prevails, but more often drivers are faced with every type of weather from driving rain in the north and fog in the mountain passes to hot sunshine around Rome and on the Adriatic.

In 1934 it rained throughout most of the race, a feature which worked to the advantage of Nuvolari, who was driving a privately owned 2.3 Alfa Romeo against the works 2.6-liter cars. He was able to keep among the leaders for much of the race by using his superior skill on the wet roads, but he eventually had to give best to his old rival Varzi in a 2.6 and be content with second place. The MGs again took part in this event but they had to give best to Taruffi's 1100cc Maserati in the 1100cc class, the little Maserati finishing fifth overall as well.

With the accent turning to the monumental Grand Prix successes of the German Auto Union and Mercedes teams, sports-car racing lost some of its appeal in the mid 1930s, but the Mille Miglia continued successfully, even if lacking in foreign opposition. The 1935 event went to Pintacuda/della Stufa, the 1936 race was taken by Brivio/Ongarao, while Pintacuda/della Stufa won the 1937 race, all of them driving Alfa Romeos. Brivio's win shot the race average up to 75.57 mph, but he was using the 2900A which was little more than a thinly disguised Grand Prix car. The 1937 winning car was a 6C 2300 with a special duralumin body.

For the 1938 race some changes were made to the route. This was as before down as far as Florence, but then the cars were taken westward to the coast which they followed all the way to Rome. The 1938 race was a tragic one which nearly caused. the abandonment of the event. A car plunged into the tightly packed crowd near Bologna, killing ten spectators and injuring a further thirty. The race waswon by BiondettiJStefani in a production version of the 2900A

Alfa Romeo called the 8C 2900B, at an average speed of 84.13 mph.

Mussolini Ban's The Mille, So It Is Re-Named The Grand Prix of Brescia

Italy's dictator, Mussolini, bowed to public opinion after the tragedy and banned the race for 1939· Despite the onset of World War 2, Renzo Castagneto, who still organised and acted as starter of the race, decided to run the Mille Miglia in 1940, expressly against Mussolini's wishes. He was restricted to a 193-mile triangular course, running from Brescia to Cremona to Mantua and back to Brescia, and the event was named the Grand Prix of Brescia, although it was also listed in the programme as the 13th Mille Miglia.

Despite the wartime conditions the Grand Prix of Brescia attracted a team of 2-liter BMWs from Germany and the very first Ferraris, the type 815s, which were little more than rebodied Fiat 1100s. Significantly, one of the 815s was handled by 20-year-old Alberto Ascari, then setting out on his illustrious career. The works Alfas and the Ferraris all ran into trouble and it was the works BMW of Huschke von Hanstein and Baumer that won the race at an average speed of 103.60mph.

The war put paid to the Mille Miglia for six years, but Castagneto was determined to get the race going again. This proved to be a difficult task, as Italy had been ravaged by the war. In fact, when Castagneto attempted to drive round the route he was met by fallen bridges, great holes in the roads and complete devastation. But he persisted and finally announced that the race would be run in June 1947. Over 100 entries were received for the 14th Mille Miglia, included among them being the new 1½-liter Ferrari, Villoresi with a 2-liter Maserati and a host of the tiny new Cisitalias, one of which was to be driven by Nuvolari himself, at the age of 55, despite suffering from a serious chest complaint.

The route had been modified considerably, the main change being to reverse the direction of the race so that it now ran clockwise round Italy, leading from Brescia down the Adriatic coast, then across to Rome, returning northwards across the Futa and Raticosa passes to Bologna and then deviating through Asti, Turin and Milan before rushing back to Brescia along the autostrada. This increased the race distance to its longest ever figure of 1133 miles.

Nuvolari was given little chance in his tiny cycle-winged 1100 cc Fiat-engined Cisitalia, but even though the circuit now went the 'wrong' way and the ailing Nuvolari had had little chance to survey the route he once again began to throw his car around, to the great terror of his mechanic, Carena. By the time they reached Rome Nuvolari had built up a lead of no less than seven minutes over the 2.0-Iitre Alfa Romeo of Bicindetti. Over the fogbound Futa and Rarticosa passes, which Nuvolari could drive over with his eyes closed, he extended his lead and although Biondetti closed up on the level ground towards Florence, Nuvolari still had a nine minute lead when they reached Bologna.

Nearing Asti the Cisitalia rushed through a deep puddle and suddenly the engine stopped; Carana and Nuvolari desperately dried out the ignition, but they had lost fifteen minutes by the time the engine was running again. The exhausted Nuvolari once again began driving like a maniac although the rain had by now turned to hail and the open cockpit of the Cisitalia had been turned into a mobile swimming pool. But with the fast straight roads of northern Italy to come there was little that even Nuvolari could do about the big Alfa and the Cisitalia rolled into Brescia 16 minutes behind Biondetti.

Nuvolari is offered a 2-liter Ferrari by Enzo

However, it was enough to convince Italian enthusiasts that the 'Flying Mantuan' was back at the top. Nuvolari was to make one more glorious attempt at the Mille Miglia; he was offered a 2-liter Ferrari by Enzo Ferrari for the 1949 race, an offer which he gladly accepted. He started off more gently than usual, but he got into the lead as soon as the cars reached the Appennines and began to pull away from everyone else. His great rival, Biondetti, who was also in a factory Ferrari, conserved his car in the mountains, but Nuvolari pushed as hard as he could and at Rome he was 12 seconds in front of Alberto Ascari.

Then Ascari retired and, over the Futa and Raticosa passes, Nuvolari pulled out an enormous lead of nearly half an hour. But the Ferrari was falling to bits around him; first the bonnet flew off and disappeared over his head down the mountainside; then his seat began to break up and after enduring the sliding sensation on every bend he threw the wrecked seat away and sat on a couple of bags of lemons and oranges. His pace hardly abated even though he was far in the lead and when he hit a pothole at over 100 mph, the car broke a spring shackle completely. He arrived at Bologna with a 35-minute lead over the canny Biondetti, but the bodywork was falling apart and the chassis itself was beginning to break up.

The mechanics took one look and told him to retire, but he gave them a rude sign and drove back into the race. But the car couldn't last much longer and when the rear brakes stopped working, nearly causing several accidents, Nuvolari was finally forced to retire at Villa Ospizio, once again completely exhausted by his efforts and the results of his illness, which was finally to kill him four years later. Biondetti won the race as expected and went on to take his fourth victory the following year when the circuit was again run anti-clockwise.

The Bologna section was cut out, the cars being routed down the Mediterranean coast resulting in the race distance was reduced to 990 miles. It was in 1949 that the unique system of race numbering was instituted; the cars were numbered according to their starting time so that a car starting at at 5.30 am was numbered 530 and so on. This enabled spectators to check on the progress of various cars.

Italy was becoming fully conscious of the motor car in the early 1950s and, although many still had to rely on the ubiquitous Lambretta scooter, a large number of people could afford a Fiat 500 or other small car and it soon became a point of honour among enthusiasts to enter the Mille Miglia. In 1950 the official entry list contained 743 starters, including many foreign entries, but it was not unheard of for keen drivers, who did not have the price of the entry fee, to slap some numbers on their road car, join the race at some deserted spot, dice happily down the route for an hour or two, then slip off at another deserted spot and motor contentedly home.

Virtually everything on four wheels could be entered for the early post-war Mille Miglias and many drivers could be seen bowling along for hour after hour in tiny Isetta bubble cars and other tiny contrivances. They naturally caused a great deal of trouble to the faster cars which had to overtake literally hundreds of slower cars and many collisions were caused by slower cars. However, the faster drivers accepted the problems, simply because it was the Mille Miglia, but several of the Grand Prix aces refused to have anything to do with the race and even the great Juan Manuel Fangio was none too keen on the race.

The Foreigners Re-Join The Race

In 1950 the race reverted to a clockwise direction and it remained this way with minor alterations until the final event of 1957. The race came under attack from foreign teams once more, principally Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar; the firmly-sprung Jaguars seldom lasted long, but Karl Fling finished second with a Mercedes 300SL in 1952 behind Bracco's Ferrari. Stirling Moss got his Jaguar up to third place in 1952 before crashing and in 1953 Reg Parnell finished a fine fifth in a factory DB3 Aston Martin. A feature film called Checkpoint was eventually made, using the Aston Martin cars and the race as its background.

In 1953 the Mille Miglia became a qualifying round in the newly instituted World Sports Car Championship. This forced the organisers to weed out some of the slower cars, but in turn it also obliged racing-car manufacturers to enter the event if they wished to gain points in the Championship. The Ferrari stranglehold on the race, which had held since 1948 came to an end in 1954 when Alberto Ascari won in his 2.3-Iitre Lancia ahead of Marzotto's Ferrari. Both works Astons crashed in the race and Jaguar decided not to compete.

For the 1955 event Mercedes were determined to win with their 300SLR; they spent a great deal of money in preparing cars and giving their crews extensive opportunities for practising on the route. Stirling Moss was paired with British journalist Denis Jenkinson, who prepared a comprehensive set of pace notes so that he could signal the severity of bends to Moss. The system worked perfectly and Moss won the race at an average speed of 97.89 mph, nearly 10 mph faster than the previous race average.

To maintain almost 100 mph over the undulating terrain of Italy seemed an impossible task before the race, but the 170mph Mercedes never faltered once and Moss was able to push hard for ten hours. Castellotti in a 4.4-liter Ferrari drove single-handed and bravely against the Mercedes, but he wore out his tyres too quickly and eventually blew up, while Piero Taruffi, who led briefly in a 4.9 Ferrari also retired. Fangio showed his quality by finishing second to Moss. In a way the very speed of the Mercedes victory led to the demise of the Mille Miglia, for it suddenly became very apparent to disinterested parties in Italy that hundreds of cars were rushing about Italy at speeds of up to 170 mph, passing through throngs of completely unprotected citizens.

Portago's Crash That Ended The Famous Race

Agitation for the abolition of the race began to grow. The 1956 race took place as planned in early April and Castelotti gained his revenge, winning a very wet race at 85-40 mph, while Britain's Peter Collins finished second in another 3.5-liter Ferrari. The best Mercedes could do this time was sixth. The 1957 event proved to be the last. Peter Collins led the race for a spell, in a Ferrari, but rear axle trouble put him out, while the Moss/Jenkinson partnership lasted only a few miles before the brake pedal snapped off in their Maserati.

With Collins's retirement, Piero Taruffi got into the lead and, despite a grumbling transmission, the car held together to give Taruffi his long-awaited victory. Unfortunately, soon after Taruffi finished came the news that Count Alphonso 'Fon' de Porta go had crashed his Ferrari only thirty miles from the finish. A tire had burst and the Ferrari had scythed into the crowd at maximum speed killing Portago, his navigator and nine spectators. The rising tide of public opinion soon forced the Government to prevent the race being held again. This time Renzo Castagneto was obliged to give in, although a couple of regularity rallies were held in 1958 and 1959 with the title of Mille Miglia. These attracted little interest and the Mille Miglia was no more.

In 1982 the Mille Miglia endurance race was revived as a road rally event. Nowadays, timing rather than speed is of the essence for the enthusiasts from around the world who race their vintage cars, dating from 1927 to 1957. This magnificent parade of classic machines has earned the Mille Miglia the reputation of being "the most beautiful road race in the world". Every May, Brescia becomes the meeting place for the rich, famous and passionate as they prepare to do battle over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of Italian roads. The event is closely followed by the press and immortalized every year by one of world's most respected photographers, Giacomo Bretzel, whose images so perfectly communicate the intensity, the emotion and the spirit of the moment.

Further Reading: Mille Miglia Winners Table (AUS Site)