Introduction

Born in 1912, Whitney Willard Straight was one of the very few American drivers to make his mark on the European competition scene, a fact which is all the more remarkable for the fact that his racing career encompassed just four years before he retired in 1935 to begin a brilliant career in civil aviation.

Whitney Straight was still an undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge, when he began racing at

Brooklands, in August 1931. His mount was an 1100cc Riley which he had tuned himself. Straight, however, was no penniless amateur mechanic, for he possessed a sizeable fortune and was already an accomplished pilot. On one occasion, he created a stir by fitting in a University examination and a Brooklands meeting all in one day, flying from Cambridge to Weybridge in his private aeroplane.

He enjoyed moderate success with the Riley, taking fourth place in his first race, plus a number of thirds in events at Brooklands, Shelsley Walsh and South port, but he was already looking for a faster car. With a borrowed Bugatti, he dead-heated for first position in the Norfolk Mountain Handicap at Brooklands in March 1932, then bought Sir Henry Birkin's Maserati, which held the record for the Mountain Circuit at the track.

On 26 May 1932, Whitney Straight drove this car to second place in the Nottingham Mountain Handicap, managing to break the existing lap record in the process. Straight found that motor racing was proving an extremely expensive hobby, even for a millionaire, and decided to organise his sporting interests on a business basis, as he felt that racing might pay for itself, if properly promoted. So, late in 1933, Straight set up a motor-racing stable, established in Milan, with an office in Bush House, London, staffed by Bill Lambert, who had formerly been Birkin's private secretary for a decade.

Five of the stable's mechanics were ex-Birkin men, too, and worked under the supervision of Guilo Ramponi. The cars to which they attended were three 1.5-litre Maseratis, one of which had been originally intended for Tazio Nuvolari, who had crashed at Alessandria and therefore been unable to take delivery. The cars cost £2000 each, but Straight had another £1000-worth of work put in on each Maserati before he considered they were ready to race. The cars were totally rebuilt, with special bodies, pre-selector gearboxes, new petrol and oil tanks and reworked suspension and cooling systems.

As Straight's policy was to enter the cars for as many events as possible, each one was equipped with its own transporter complete with all necessary tools and equipment. Straight's drivers, H. C. Hamilton and R. E. L. Featherstonehaugh, were paid salaries, plus a percentage of any prizes or bonuses; the same arrangement applied to the mechanics. At the same time, the MG Magnettes owned by

Dick Seaman and Hamilton were brought into the scheme. These enjoyed the full back-up services of the mechanics and their drivers took a percentage of any winnings. During the season, the cars raced in England (where

Whitney Straight came second in the Nuffield Trophy and won the Brooklands International Trophy and the Donington Park Trophy), Switzerland (where he won the Prix de Berne), South Africa (where he took fifth place in the East London GP and won the South African GP), Czechoslovakia, Monaco, Tripoli, Germany, Morocco, Italy, France, Algeria and Spain, enjoying a good deal of success.

However, Straight's attempt to make a business out of motor sport suffered a tragic setback when Hamilton was killed in a crash during the Swiss Grand Prix; the smashed Maserati was sold for £100. Thus, when Straight came to balance the books at the end of the year, he found that the team's income totalled £10,325, and expenses were £13,100! It was, however, impossible to continue the venture into 1935, as Straight's business interests in civil aviation were now claiming all his time. Straight's career spanned only four years.

From Reluctant Millionaire To Hero Of Brooklands

Since Germany's pre-war Grand-Prix teams were primarily instruments for Nazi propaganda, it was understandable that Mercedes and Auto Union didn't exactly trump up excuses for hiring drivers of English speaking nationalities. Contrary to the facts, it is generally believed that Britain's Dick Seaman was the only man in this category who ever signed a contract to race under the invincible swastika. Actually, American born Whitney Willard Straight did, too. Up to a point, but only that far, there was a background similarity between the enlistment of

Dick Seaman by Mercedes and Straight by Auto Union. The Englishman, under pressure from fond parents to resist the German bait and embrace a safer profession, hardened his heart, signed, raced, and finally crashed to his death in the 1939 Belgian Grand Prix.

Straight signed first - this was in December of 1934 - and did his arguing afterwards. Mrs. Whitney Willard Straight, using the leverage that is nature's endowment of young and beautiful wives, won this verbal wrestle in a single throw. Straight thereupon tendered his apologies to Herr Willy Walb, head of Auto Union's racing department, and secured a release from his agreement. He never raced again. In the six-year period of Germany's state sponsored fling in the Grands Prix - 1934 to 1939 inclusive - Mercedes and Auto Union between them used the services of 25 drivers. Nineteen of them were German, three Italian, one French, one Swiss and one British. To rate a come-hither from Unterturkheim or Zwickau, it wasn't enough for an Englishman or an American to be good - they had to be sensational. And that's what Straight was, in common of course with Seaman. But while history does ample justice to the memory of

Richard John Beattie Seaman, a generation of motor sport enthusiasts grew up having hardly heard of Straight - and as time has progressed even fewer know of his incredible ability.

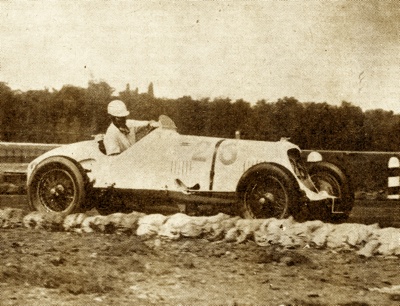

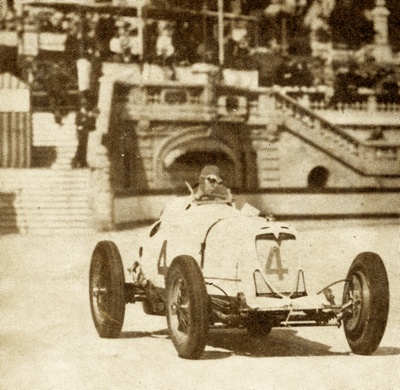

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati.

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati.

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati.

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati.

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati.

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati.

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati.

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati.

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati.

Whitney Straight after winning the 250-mile JCC International Trophy Race at Brooklands in his 2.9-liter Maserati. |

Learning The Trade

Whitney Willard Straight's rise from nowhere to the top of the heap was like a tracing from a mortar trajectory. With the possible exception of

Prince Birabongse of Siam, whose career only just overlapped with his, Straight learned his trade faster than any of his contemporaries. It took Seaman six years, devoted with singleminded passion to racing, to acquire the skill that won him his Mercedes berth; Straight on the other hand had been in the business less than four years when Auto Union wooed him into that stillborn contract.

In his first year of speedwork, 1931, at the age of 18, Whitney Straight drove in six events and finished third in five of them. But as most of these were merely 1100 c.c. class or handicap placings (his car was a

Brooklands Riley he had tuned himself) they didn't set the Thames on fire. About the only quarter in which, at this early stage, the youth made a strong impression was among female race fans, who reacted with cardiac backfires to his extreme good looks, almost bordering on prettiness.

The Brooklands Mountain Circuit

During the following winter Straight unloaded the Riley and replaced it with a 2.5 litre Grand Prix Maserati, which he bought from

Sir Henry (Tim) Birkin, Britain's top racing star at that time. The effect was electrifying. During 1932, with about as much experience in his whole body as Birkin had in his big toe, Straight blasted the baronet's record for the Brooklands Mountain circuit by the incredible margin of 2.79 miles per hour. Both drivers having used the same car, this performance put their respective skills into true and awe inspiring perspective.

For 1933 Straight raised his sights and launched out into an ambitious programme of British and Continental races and hill-climbs; he retained the 21 litre Maserati but widened his scope by acquiring a supercharged MG Magnette for a strike in the hotly contested voiturette field. Again the impact was stunning. Witn the Maserati he won the Brooklands Mountain Championship from Piero Taruffi, winner of the 1957 Mille Miglia.

He

slashed more than 40 seconds of

Rudolf Caracciola's record for Mont Ventoux, longest and most difficult speed climb in Europe; was the first to undercut Hans Stuck's record at Shelsey Walsh, a prize that had been tantalising England's hill-climbing elite for three years; placed second in the Albi Grand Prix (he would have won it if the Bugatti opposition hadn't ganged up and subjected him to a racelong pincers movement); and set a lap record before retiring with a broken gearbox in the International Trophy at Brooklands.

The Coppa Acerbo

On the K3 Magnette at Pescara, Italy, he won the Coppa Acerbo and, on returning to England, rounded off the season with two second places against star talent on the Brooklands Mountain course. An American being a rare bird on the Old World racing scene, and specially one combining movie-star good looks, great wealth, ancient lineage and the prowess of a budding

Tazio Nuvolari, British newspapermen and magazine writers showed a wholesome interest in Whitney Willard Straight.

It was disclosed, for instance, that his English forebears had for 600 years been lords of the manor at Whitnew-on-Wye, Herfordshire, before emigrating to America early in the 17th Century; they'd really only intended making a round trip of it but changed their minds and stayed over. Young Whitney's mother, widowed but now married to an Englishman, had brought the boy to England when he was 12. In addition to his gifts as a driver, Straight was also an accomplished air pilot, photographer, painter, pianist, 'cellist, saxophone player, skier and underwater fisherman.

Among his distinguished and/or noble kin he could count Jock Whitney, recently U.S. ambassador to Britain, who was a first cousin; Lord Queenborough, an uncle; and the Hon. Dorothy Paget, another first cousin, who was Sir Henry (Tim) Birkin's backer when he was racing the famous blower Bentleys in the early 1930s. Straight was resident at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was reading for a philosophy degree. By way of a test of his personal philosophy, a university edict was in force forbidding first year students to drive cars on the street.

For private transportation he therefore alternated between a pedal bike and his own plane, using the former for local peregrinations and the latter to shuttle rapidly between Cambridge and the various theatres of motor sport. Cost being no object, and Straight being a man who never cared to leave a stone unturned, it was his custom when flying to the circuits on a tight schedule to have himself tailed by an escort aircraft, just in case of forced landings en route.

Boy Millionaire Race Track Idol

Normally of a quiet and courteous disposition, Straight nonetheless had one raw spot: he hated allusions to his wealth. This must have kept him busy hating, because the sight of his name in a typescript was enough to set subeditors reaching for stock headings like "Boy Millionaire Race Track Idol". One columnist quoted him as saying "I often wish I never had a fortune. It is difficult to make real friends and nobody appreciates you at your true worth".

To establish his worth in his own eyes, he once cut loose from luxury for awhile and lit out into the English country-side on an old motorcycle with only a few shillings in his pocket; over an unspecified stretch in the role of a mechanised hobo, he claimed he had earned 30/- a week as a stonemason's labourer. But there were moments, it seems, when even this modest competence oppressed him; in the summer of 1933, around the time when he was just starting to louse up the lustre on such names as Birkin and Campbell, he confessed he was thinking of renouncing all his worldly possessions and retiring into a monastery for the rest of his life.

That Straight's qualities as a driver were genuine, and not just chimera conjured up by the glamour-drunk hacks of Fleet Street, can be verified by consulting such austere authorities as "The Motor" and Capt. George Eyston. Writing of Whitney's Coppa Acerbo exploit in 1933, "The Motor" said "the result staggered the natives for there was exceptionally stiff Maserati opposition". Incidentally, although Straight won this race by only a fifth of a second, it wasn't quite the closest thing of his career; the previous year, driving a borrowed Bugatti in a Brooklands Mountain race, he had dead-heated for first place with another driver in a Bugatti. There were only about three ties in the entire 32 years history of

Brooklands.

Motor Racing and Record Breaking

Following Straight's Mont Ventoux triumph, recalled earlier, sobersided "Motor Sport" classified this upshot as "a performance which will rank as the outstanding achievement of its kind during 1933". And

George Eyston, in his book entitled "Motor Racing and Record Breaking", had the following to say about the reluctant millionaire: "The ability necessary to run successfully in important Grands Prix can usually be acquired only by constant driving in lesser events ... Yet occasionally a driver will appear who is so gifted that, with very little experience, he can challenge men with years of race experience behind them. Such a man is Whitney Straight".

Paradoxically, in spite of Straight's avowed distaste for riches, it irked him to run his racing affairs on a non-paying basis. This was the footing on which most, if not all, of his British friends and rivals per-forcedly ran theirs, and for two reasons: one, by sacred precedent, the English race promoting bodies of the day never paid a penny of starting money or expenses to their own nationals or to foreigners who, like Straight, were domiciled in Britain. Two, although there were a few English drivers who habitually travelled to the continent to race, the relative inferiority of their equipment gave them a mediocre starting money rating, and anyway their self-imposed standard of gentlemanly conduct was liable to be an obstacle to sordid bargaining.

Whitney Straight Ltd.

Straight, unencumbered by such scruples, and adequately heeled to ensure that his equipment wasn't inferior, resolved to intersplice pleasure and business. In preparation for 1934 he, therefore, floated a company, Whitney Straight Ltd., and, upon this structure, set up the first Continental-style scuderia ever to operate from the U.K. Although, as it developed, the stable's lifespan was limited to one season, owing to its founder's grievously premature retirement, it did things on a big scale while it lasted. Swank offices were leased in one of London's most expensive hubs of commerce, and presided over by a former factotum of Sir Henry Birkin, one Bill Lambert Three brand new G.P. Maseratis, of the latest three-litre type designed for the 759-kilogram formula that was inaugurated in '34, were bought from the Maserati brothers in Bologna.

As Continental meets predominated in the schedule Straight had mapped, the cars were based, and elaborate workshops established, in Italy: to be exact, at Milan, conveniently close to Bologna. An experienced staff of mechanics, five of them former Birkin employees, were engaged and put under the orders of the celebrated Guilio Ramponi, co-driver of the

Mille Miglia winning Alfas in 1928 and 1929. Under Ramponi's supervision, and with aid from Reid Railton, radical modifications were carried out on all three cars before they were considered ready for the fray. These included the replacement of the makers' crash type gearboxes with preselector jobs of

Armstrong Siddeley design, and the transformation of the front ends by fitting special cowls to Straight's own drawings. As delivered, the 8 cylinder 65 by 100 millimetre engines developed 265 b.h.p. at 5,800 r.p.m., giving these single seat cars a top speed of around 165 m.p.h.

Hugh Hamilton and Buddy Featherstonhaugh

Campaigner members of the scuderia, apart from Straight himself, were Hugh Hamilton and Buddy Featherstonhaugh, Englishmen both. Hamilton was already rated among Britain's top three drivers, but it is doubtful whether the latent virtuosity of Featherstonhaugh had been recognised by any one but Straight up to that time. It was a shared interest in the homely saxophone, on which Buddy was an internationally renowned tootler, that originally had brought him and Whitney together. Featherstonhaugh's Maserati fingering proved at least equal to his sax technique, as he demonstrated by beating Hamilton into tne winning spot in the 1934 Albi Grand Prix. If it hadn't been for the liquidation of the stable at the end of that season, this discovery of Straight's, like Straight himself, might eventually have rivalled the fame of

Dick Seaman.

Dick, by this token, although not under formal contract to Wnitney Straight Ltd., did in fact string along with the stable on its frontier hopping travels, and shared its facilities and services.

Seaman and

Straight had entered Trinity College, Cambridge, in the same term, two years earlier, and been close friends all along. The American's rise to racing stardom had of course preceded Seaman's, and although Whitney played down the suggestion that his influence and example may have had a significant effect on the course of Dick's career, many people thought otherwise. The bare statistics of Straight's personal record in Continental Europe and Africa during 1934 do less than justice to his absolute brilliance as a driver. This for two reasons: then as now, even the best equipped independent was constantly one move behind the works drivers as far as cars were concerned.

James Robertson Justice

Two, although the Milan establishment admittedly was well staffed and richly appurtenanced, the programme of races undertaken was so large and far-flung that even these resources must have been strained at times. Straight himself contested no less than 10 Continental meets, six in England, three in North Africa and one in South Africa, as well as making two successful record bids at

Brooklands on no-race occasions. That made it 22 engagements in one season, involving vast intermediate mileages, and took no account of involuntary non-starts through mechanical unreadiness or blowups during training. In the early phase of the enterprise, incidentally, the job of pit manager was handled by a man whose name, face and beard were to become familiar to international audiences - James Robertson Justice, a movie actor, whose roles have included the millionaire equipe owner in "Checkpoint", an improbable piece about an imaginary race in the

Mille Miglia manner. Justice wasn't a very good pit manager and Straight fired him.

Twice in 1934, when facing opposition from maestri of the Alfa and Maserati persuasions, Straight placed fourth, just out of the money. In the first of these encounters, the Casablanca Grand Prix, he was only beaten by the great

Louis Chiron (Alfa), then at the height of his legendary form, Phillipe Etancelin (Maserati) and Marcel Lehoux (Alfa). The other time, in the Montreux G.P., the placemen were Count Trossi (Alfa), president of Suderia Ferrari, Etancelin again, and Achille Varzi (Alfa). Then, as the season went on and Straight gained in confidence and racecraft, he did better still. After winning his heat of the Vichy Grand Prix, ahead of Lehoux, Rene Dreyfus (Bugatti) and the then youthful Guiseppe Farina (Alfa), he finished second to Trossi in the final. The Com-minges G.P. brought him a hard earned third, two places up on Jean-Pierre Wimille, while in the classic Italian Grand Prix, dominated by the Mercedes and Auto Union teams, he took a fraction of a second longer than the lowest placed Auto Union (Mom-berger and Sebastian) to cover Ihe 311 miles.

Becoming A British Citizen

It may well have been this performance that opened the eyes of Herr Willy Walb to Straight's potentialities, the Auto Union being decisively a faster car than the privately owned Maserati. Back home in the land of his adoption - he had meanwhile become a British citizen - Straight's successes were spectacular. At Brooklands he won the 260 mile International Trophy, repeated his 1933 victory in the Mountain Championship, raised his own Mountain circuit lap record yet again, and broke the International Class D records for the flying mile and kilometre at 135.-19 and 136.98 m.p.h. These figures, much to the credit of Ramponi, established the pick of the stable's Maseratis as the world's fastest 3 litre car. At Shelsley Walsh, Straight lopped 1.2 seconds off his own record for the 1,000-yard hill; it was not beaten for decades.

Straight only once drove an American car in competition and it gave him the biggest scare he ever had on wheels. In 1934, Scuderia Ferrari sold him a 4.3-litre

Duesenberg that Trossi had driven in the 1933 Monza Grand Prix. Originally built for Indianapolis, this was a real brute of a car with a mean disposition. Showing remarkable courage, Straight undertook to use it for an attack on the main circuit lap record at

Brooklands, standing to

John Cobb and the 24-litre Napier Railton at 140.93 m.p.h. And on October 13, 1934, in one of the stoutest exhibitions of unarmed combat the old track had ever seen, young Whitney turned a lap at 138.78 m.p.h. - a shortfall of 2.15. When you allow for a displacement handicap of 19,594c.c., and the fact that the

Duesenberg, with chassis rails seemingly made of jelly, was most of the time going one way and pointing another, the failure is seen as an honourable one. Anyway, it set a Class C lap record which, in the remaining five years of the circuit, was never beaten.

A Natural Driving Ability

His fast mental reaction in racing crises was an integral part of the Whitney Straight legend. Twice during 1933 his quick wits saved him from at least a severe roughing up, possibly worse, and carried him scatheless off the scene of a ruckus. The first time was at Vram in the Swedish Summer Grand Prix, where he was driving a borrowed Alfa. At an early corner on the first lap, eight cars tangled violently, one of them somersaulting and catching a house on fire at the roadside. Straight and Louis Chiron, who had drawn back-row positions in the ballot for grid precedence, came around a blind curve and found themselves headed for the pyrotechnic picnic at high speed. Whitney Straight picked a path through the flames and debris (a riding mechanic had been killed), and went on to place second to Antonio Brivio of the Ferrari Alfa team. As he entered the wreck zone, Straight had taken time for a quick peek in his mirror - and seen

Louis Chiron, who wasn't exactly a cerebral sluggard himself, diving off into a ditch.

The other occasion was at Brooklands in the Mountain Championship. The title holder,

Malcolm Campbell, built up a quick lead on the first lap, then spun and stalled his four-litre V12 Sunbeam across the track at a point where it couldn't be seen my oncoming drivers until too late for evading action. Tim Rose-Richards, first on the scene, set about establishing a ferrous stockpile by leaning his Bugatti on the Sunbeam. At that, officials on the spot rushed to a better signalling base and waved frantic warnings to a group of four who were approaching like the hubs of hell. Three of them - and these included Piero Taruffi interpreted these calisthenics too literally for their own good. Seizing his chance while they were still in their brown study, Whitney went under their elbows and into the lead, holding it. to the finish.

Scuderia Whitney Straight had a grievous bereavement of its own the following summer, when Hugh Hamilton crashed fatally on the last lap of the Swiss Grand Prix at Berne. What was left of the Maserati he was driving would never have gone together to make a racing car again, so it was sold for scrap metal for a few pounds. Of the two three-litre Maseratis that survived the dissolution of Straight's company, one was sold to

Prince Birabongse (

B. Bira) and started on a new and triumphant lease of racing life, and the other was made over into a dreamboat of a sports two-seater to its owner's body design. The ex-Bira car continued as a pacemaker in vintage races around the airstrips and circuits of England through the 1950s.

Hill-Climb Specialist

Although, as his dossier shows, Straight was certainly no dawdler in widely differing forms of go-around racing, he perhaps excelled above all as a speed hill-climber. As well as having a natural aptitude for the specialised technique used in overcoming Sir Isaac Newton's well-known iaw, he made a smart move at the outset by having his first Maserati (and, of course, the subsequent ones) fitted with a preselector gearbox. This was an invaluable aid on the close pitched and usually tight turns xeatured in hillclimbs, whether of the putt-length English variety cr in the continental manner as ex-ampled by the 13J-miie mountainside ascent of Mont Ventoux. For another thing, too, he always ran in climbs with dual rear wheels, thereby doubling traction. It was largely tne combination of these two features that enabled him to administer such awful punishment - a 40.8 second cutback - to Caracciola's Alfa record at Ventoux in 1933.

Straight never actually got into the lineup of a sports car race, but only just not: at

Le Mans in 1934, he and Prince Nicholas of Rumania were paired to share the biggest car in the entry, a blown

Duesenberg about a parish and a half long. It ran into mechanical woe during practice and so didn't start. Dimensionally, this

Duesenberg was probably the biggest car Straight ever drove, but not the biggest in displacement. As a street driver, in fact, he was quite a glutton for litres. When, for instance, he inspected the wares of

Hispano-Suiza with a view to purchase, and discovered that their V12 Bolide went only 91 litres, he trousered his cheque book in disappointment. However, not to be done out of a sale, Hispano did a boring and stroking job that yielded 11 litres, so the deal was on after all.

Commander of the Order of the British Empire

Two of these monsters, with bodies by Fernandez and Darrin that certainly couldn't have been bought out of a stonemason's pay pack, were built, one for Straight, the other for Count Carlo Felice Trossi. They were so heavy that no power-on earth would stop them, so Whitney stopped driving his, thereby surviving to serve with great distinction in the R.A.F. during the Second World war (Commander of the Order of the British Empire, Military Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross), and to attain his eminence in the world of aviation and commerce.

Also see: Whitney Willard Straight (AUS Edition)